A reintegration plan is a tool for returnees to identify their objectives for their reintegration process and to plan, with the support of the case manager, what support is needed and how it will be provided. The plan is developed by bringing together an understanding of the returnee’s skills, needs and motivations and the context of the return environment, including its challenges, opportunities and available services. A reintegration plan should be developed for each returnee that is being assisted by a reintegration organization.

There are four main steps for developing and implementing a successful reintegration plan:

- Review and analyse the returnee’s own objectives and motivations for the reintegration process (elicited in Step 6 of the first counselling session, see section 2.1.1) together with findings from individual assessments (see section 2.2) and information from the context assessments (see section 1.4.2);

- Use the feasibility grid, or another tool, to identify appropriate support activities, covered in section 2.3.1 (see section 1.4.3 for information on developing feasibility grids);

- Draft the full reintegration plan, covered in section 2.3.2 (suggested template can be found in Annex 3);

- Establish regular follow-up, covered in section 2.3.3.

While it is preferable that reintegration plans be developed or refined within one month of a migrant’s return to their country of origin, it is also preferable that individual programmes have the option to maintain some leeway when it comes to time frames and time limits. Different migrants have different needs and cannot always adhere to the same reintegration assistance structure, especially migrants those who have vulnerabilities. This can become a challenge when funding sources impose rigid rules around eligibility and place the full burden of responsibility on the returnee. Advocating for exceptions to rules and flexibility in timelines, when necessary, is therefore important.

This chapter provides further details on developing and implementing a reintegration plan, supported by further guidance in the annexes:

- 2.3.1 Using the feasibility grid

- 2.3.2 Components of an individual reintegration plan

- 2.3.3 Reintegration planning and follow-up

2.3.1 Using the feasibility grid

Section 1.4.3 guides staff through the process of developing feasibility grids in a reintegration programme. This section guides case managers through the use of the grids, once developed.

The feasibility grid is a tool that the case manager can use when helping a returnee design an individual reintegration plan. It lays out various alternatives for addressing the returnee’s economic, social and psychosocial needs and the conditions under which those interventions are most appropriate. The full reintegration grid can be found in Annex 5.

The feasibility grid guides the targeting of assistance, which is the activity of selecting reintegration services for returnees, their families or their communities based on individual circumstances and the barriers faced in reintegration.

Case managers should tailor reintegration support measures for returnees in modular form. In practice, this means that reintegration services should be adapted in terms of type, duration and intensity to the returnee’s and to the family’s needs, capacities and intent. For instance, while a skills’ assessment coupled with a three month TVET programme might be useful for one returnee, another returnee may only need a referral to a local public employment service office for job matching and successful labour market reintegration.

2.3.2 Components of an individual reintegration plan

The format of an individual reintegration plan varies from context to context and organization to organization.

But it can be modelled on the recommended template in Annex 3. Typically, the following components should be addressed, covering the economic, social and psychosocial aspects of reintegration:

- Financial allocations (cash or in-kind assistance, see table 2.2)

- Income-generating activities

- Vocational training or apprenticeships

- Housing, food and nutrition

- Legal and documentation needs

- Education and skills’ development

- Medical and health-related needs

- Transport

- Security

- Psychosocial needs

- Family needs and counselling

The reintegration plan should incorporate the information gathered during the needs assessment and provide an overview of the services returnees will need to access, including relevant contact details for service providers. It should include information on how and when the case will be monitored, how feedback from the returnee will be incorporated and how information will be shared between the returnee, the case manager and other service providers, accounting for privacy and confidentiality.

Reintegration plans should additionally estimate how long returnees need to access services. When possible, they should incorporate information on case management exit or completion. Transition to mainstream services should be discussed if relevant (for example, for people with long-term medical or psychosocial needs). Consent forms should include all components and be updated each time the plan is amended.

Referral to existing services

Effective case management depends largely on strong linkages and referral mechanisms in the place of return. Referral mechanisms are formal or informal ways to (re)establish networks with existing organizations, agencies and providers. The ultimate aim of coordinating services by establishing linkages, is to provide access for beneficiaries to a continuum of services recognizing that rarely a single organization will be capable or appropriate to meet all of an individual’s needs. In the context of return, a referral occurs when a case manager guides a returnee to a service with the intention of meeting their reintegration needs. The referral process should include:

- Documentation of the referral;

- Consideration for privacy, data protection and confidentiality, especially for sharing personal data; and

- A follow-up process.

For more information on establishing and strengthening referral mechanisms in countries of origin, see section 4.1.3.

Cash and in-kind support

In some programmes, the direct provision of cash is a way to meet returnees’ needs while also reinforcing their agency to make decisions about how to best meet their needs. However, there are some potential risks and downsides to cash transfers. The table below outlines key questions and criteria to assist decision-making

between cash, in-kind support or a combination of both.

Table 2.2: Decision-making criteria for choice of cash or in-kind assistance options

| Level | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Programme design |

|

| Efficiency |

|

| lncentivization |

|

| Risk assessment |

|

| Conditionality |

|

| Partners |

|

| Final decision |

|

Source: Adapted from UNHCR, 2017.

Reintegration assistance when services are unavailable

Sometimes services are not available, appropriate, accessible or well-matched to a returnee’s strengths and needs. Nevertheless, the case manager still has an important role to play. All instances in which staff cannot address the needs of returnees should be recorded and monitored. This data can inform advocacy efforts at community and structural levels.

When there is a lack of services required by the returnee, the case manager can advocate for the establishment of suitable services or the inclusion of returnees in other available services if appropriate. For example, it may be possible for a woman who is the victim of trafficking to access a shelter that exists for women who have experienced intimate partner violence. When this approach is taken, it should not introduce risks or cause harm to the wider population accessing the existing service.

When there are no available services, case managers can facilitate safety planning exercises with returnees. This involves working together to identify the risks they face and developing mitigation strategies to avoid or reduce harm as well as coping strategies in the event that a risk materializes.

Where there are emergency services, for instance law enforcement, emergency health-care or fire services, and they do not pose a risk to the returnee, information on how to. access them should be provided. Where needs cannot be met, or are urgent, other options for assistance should be considered. This includes relocation to other areas where services are available.

2.3.3 Reintegration follow-up

Once agreed between case manager and returnee, a reintegration plan should be implemented. This can be undertaken by helping the returnee navigate administrative processes, accompanying the returnee to appointments, setting up meetings with officials (for example, school principals) to help with enrolments or access, and following up with the returnee.

Reintegration plans should be reviewed periodically with the returnee and adapted as necessary, especially when and if a returnee’s needs, risks or goals change. The returnee should be able to opt out of reintegration support at any time and should always have an updated copy of their own plan. Lastly, reintegration plans should always include an exit strategy that outlines when case management will come to an end and how the transition away from case management will occur.

Follow-up meetings

Follow-up meetings should occur periodically throughout reintegration and ideally for 12 to 18 months after the reintegration. plan is established to take account of any notable changes in the returnee’s life during that time. The frequency of meetings should depend on the returnee’s willingness and need, though a mid-year monitoring report (six months after the reintegration plan was initially established) and a final monitoring report for all returnees (approximately 12. months after that) is ideal.

Follow-ups are preferably conducted face-to-face. However, if in-person follow-ups are not possible they can be done via phone or email. One way to help minimize the risk that returnees will not be able to be contacted following their return, is to work with local telecommunication companies to provide communication kits to eligible returnees.

It is also helpful to use any contact opportunity to engage in monitoring and follow-up with returnees, for example when providing instalments of cash or in-kind assistance.

When a returnee’s circumstances change drastically, it may be necessary to re-administer certain individual assessments. If the Reintegration Sustainability Survey scoring system has been used as a baseline, it should be administered regularly, ideally every three months to track progress and, if needed, to adjust the reintegration plan accordingly.

Returnees in vulnerable situations should receive more frequent follow-up sessions. For example, it is recommended that returnees who are victims of trafficking be assessed once a month during the first three months post-return, then twice between months three and nine, and finally once more during the twelfth month. Should the returnee need extended assistance for any reason, monitoring should continue past the 12-month mark. Please refer to Module 5 for more details on monitoring and evaluation of reintegration assistance.

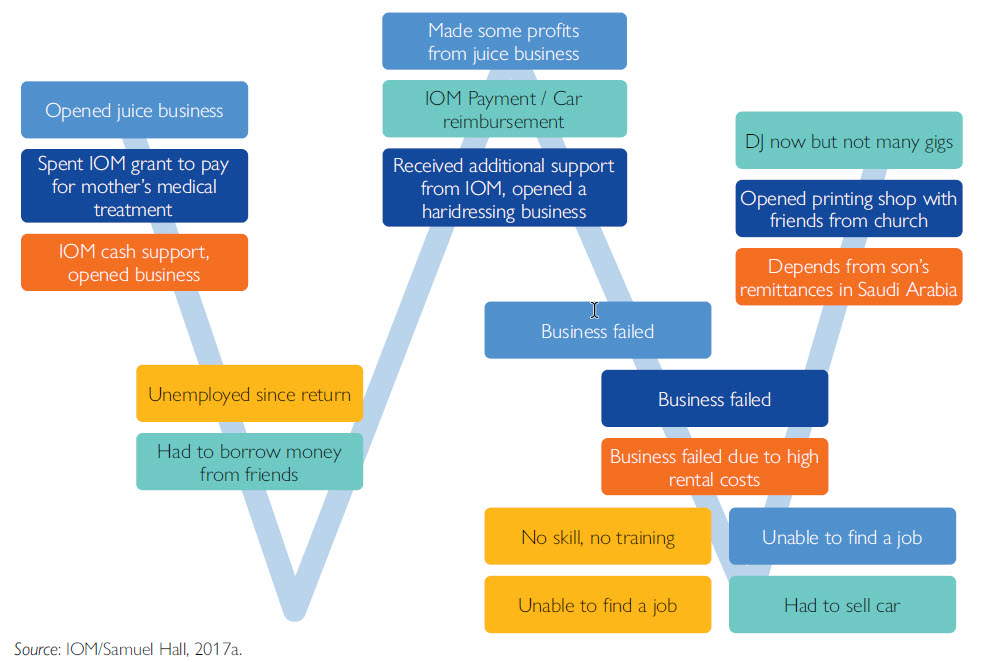

One useful tool for follow-up counselling sessions is the “W” model, which helps both identify the key challenges and opportunities experienced by the returnee, and the selection of the relevant complementary approaches to be adopted. The W model helps the case manager and the returnee with the discussion around the natural progression of “ups” and “downs” in the reintegration experience. Overall, the W model can help the lead reintegration organization identify trends in beneficiaries’ experiences as well as the unique nature of each beneficiary’s skills, capacities and social networks within a given community.

Figure 2.4: W model sample illustration

The example of a W model above was completed during a focus group session with several returnees (each individual is represented by a different colour). The session focused on the economic dimension of reintegration. As can be seen from the graph, the W model provides a good overview of the different challenges (for example, “business failed due to high rental costs”) and opportunities (“opened printing shop with friend from church”) that individuals may experience during the reintegration process. As such, the W model can be useful for individual follow-up visits at different stages of return. It is a way to identify and address returnees’ needs which arise later during the reintegration process and which require a different response than the initial planning foresaw. This allows for the reintegration plan to be updated periodically, based on the key challenges and opportunities discussed.

Case managers should refer to Annex 1.G for instructions on the development and use of the W model in counselling sessions with returning migrants.