This annex serves to expand on section 2.1 and 2.6.1 of Module 2, providing detailed guidance to case managers on counselling techniques, the do’s and don’t’s. It can be used during case manager training sessions or serve as a guide for individual case managers preparing their assistance to returnees. Section A covers basic communication techniques for counselling. Section B focuses specifically on reintegration counselling, introducing psychological techniques which would be appropriate for these sessions, and Section F is specific to career counselling.

Effective communication, proper questioning techniques, active listening, unconditional positive regard, attending and observing behaviour, barriers to effective counselling.

For counselling to be effective, the case manager should cultivate empathy, congruency, genuineness and concreteness, and unconditional positive regard. These concepts and their practical application are described below:

Empathy

It is the ability “to stand in the other person’s shoes,” aiming to look at the world through the other person’s eyes. Observing the other person’s point of view, without filtering it through personal lenses, allows avoiding a judgmental attitude and enables deeper understanding.

It is important to underline that here empathy is intended as the ability to feel “something similar” to what another person is feeling. It does not mean to know exactly how or what he or she is feeling. This is an important distinction. Examples of an empathetic approach in counselling:

- It must have been very tough to go through those events.

- I can understand that you are feeling angry at what has happened to you.

- I see that you have difficulties talking about your experiences.

- Simply sitting in silence while the person expresses their feelings or weeps.

Figure A.1: Elements of empathy

It is not enough to experience empathy; it is also important to be able to transmit empathy.

Examples of transmitted empathy in counselling:

- I am trying to figure out how you feel. I can only imagine it...

- Help me to understand how I can help you.

- I see that you are considering some options.

- I notice that you are struggling to find a solution.

➔ Empathy is different from sympathy. While empathy means “understanding” the feelings of someone, sympathy means “sharing” the feelings of someone and taking his or her side. Empathy is the correct approach to adopt when it comes to counselling. The judgement and lucidity of a case manager may be impaired if they identify too close with a returnee’s story. Sympathy can encourage the case manager to believe that they should be taking responsibility for the difficulties of returning migrant and to make false promises or create false expectations.

Examples of a sympathetic approach in counselling:

- Poor you... Your problem is very difficult to solve!

- I am astonished... It is horrible that this has happened to you.

- Be sure: I am here and I feel how difficult your situation is.

- I am so sorry for you!

- In addition, a counsellor must not be apathetic, meaning literally “without emotions”, indifferent, incapable of showing concern, participation or motivation. Adopting an apathetic approach makes the other person feel unlistened to, not understood and left alone.

Examples of an apathetic approach in counselling:

- It’s not my problem...

- Bah... I don’t know if it is possible to find a solution.

- Can you speak a little more quickly? I have another person to meet.

- Go ahead... I’m listening to you... I am just writing an email...

To recap:

Empathy involves accepting the other person’s point of view and being interested in exploring its implication on their behaviour. Sympathy involves feeling sorry for the other person. Apathy means not caring much for the other person beyond the pure mechanics of the job to be done.

Congruency and genuineness

Involves honesty and sincerity by the counsellor who does not act a role but tries to be true and authentic to themselves and to the returnee. Congruency avoids the risky approach of having the counsellor being seen as the expert, who looks down patronizingly on the returning migrant. Congruency is also crucial to obtain trust, which is the core ingredient of any helping relationship. If a counsellor behaves and feels in a congruent and genuine way, this makes the returning migrant feel at ease and allows them to be open and honest with themselves.

Examples of a congruent attitude in counselling:

- I do not have a ready-made solution, but let’s look for it together.

- I must admit that it is rare to listen to stories like yours.

- I am sorry... I do not understand what you say: can you say it with other words?

- I may seem distant, but, believe me, I am here fully listening to you.

Concreteness

Concreteness is the ability to communicate figures, facts, and information that can help the migrant to have a more complete grasp of the situation. Migrants at times do not have clear information about the real situations and rely on rumours or assumptions. Concreteness enables the counsellor to help identify the misinformation or information gaps and to help the migrant acquire a more realistic view of the situation. Concreteness helps the returnee to focus on specific topics, reduce ambiguity and channel energies into more productive paths of problem solution.

Examples of concreteness in counselling from the side of the counsellor:

- You said you want to run a bakery because you like that job. But you said you have never worked in that business, right? What actions do you think you need to take to be prepared for the challenges?

- You say you want financial support from the organization... I understand it... Do you have a plan about how to spend the money?

- The project that you describe is not clear enough to be funded: can we work it out in more detail?

Effective communication

Communication is the process of sharing information, thoughts and feelings between people through different means: speaking, writing or using body language. Communication is effective when the transmitted content – questions, statements, answers – is received and understood by someone in the way it was intended.

Therefore, the goals of effective communication include creating a common perception and understanding.

Example, from the side of the counsellor:

- Do you think I now have all the information that I need to help you?

- Is there anything else that you want to add?

- Is there any other question that you think I should ask you?

Effective communication is not only a matter of words, but entails:

- WHY those words are said – the intention behind what is said;

- HOW those words are said – the tone of voice, the way the body is used while saying those words;

- WHEN those words are said – in which context and in which moment.

The elements that make communication effective in a counselling situation are:

Proper questioning

In order to acquire information, make a good start and keep the conversation going, attention has to be brought to questioning. Asking open questions – such as “tell me about...” – helps the returnee to express themselves and guides the dialogue, which otherwise might be vague and directionless.

It is of course essential to verify at all times that the key information is correctly understood: this can be done by, for example, repeating the core messages using the words of the returning migrant:

Examples:

- M. I live with my family of seven people... two brothers and two sisters...

- C. You said two brothers, right?

- M. Yes... two brothers... one is 15 years old and the other 17...

- C. Ah... one is 15 and the other 17...

- M. I suffered terrible headaches and I had nightmares when I was in Europe...

- C. Headaches... How long have you suffered from them?

- M. If I go back to my country I will be persecuted.

- C. When you say persecuted, what do you mean?

- M. I left my little brother behind.

- C. Your little brother... how old is he?

Active listening

It is the ability of being open to the person who is speaking, attentive and focused on his or her messages. Listening actively means that it is not sufficient just to hear and listen, but it is important to show the returnee that what they say is understood. The counsellor plays an active role in the listening process and this can be shown:

- Using gestures and body language such as nodding your head and smiling;

- Using verbal affirmation such as saying “yes”, “OK”, “I see”;

- Asking questions pertinent to what the returnee has told you, to clarify your understanding;

- Paraphrasing what the migrant has said to you;

- Summarizing key points of the discussion.

Clarifying

It means to ask questions to better understand what has been heard. The purpose is to reduce misunderstanding and to ensure that the understanding of what is being said is correct. Another purpose is to reassure the speaker that the listener is genuinely interested and is attempting to understand what is being said.

Examples of clarifying:

- M. Where do I get that stuff to cook my baby’s food?

- C. What is the stuff you are talking about?

- M. I want to work… I want to attend a course…

- C. When you say “I want to attend a course” do you mean that you want to attend a course to learn job skills?

Clarification can be introduced by sentences like these:

“I’m not quite sure I understand what you are saying.”

“I don’t think that I have understood the main issue here.” “When you said [...] what did you mean?”

“Could you repeat ...?”

Paraphrasing

It means to repeat what has been heard with one’s own words and in a reduced form.

Examples of paraphrasing:

M. I lost my documents at the train station and when I went to your office your colleague helped me to get new ones

C. Ah, good! So, my colleague helped you replace your lost documents…

M. I don’t know if it is better to stay here or to go to another village...

C. You have doubts about staying or moving away… right?

Paraphrasing can be introduced by sentences like:

...you are saying that...

Do you mean that...?

Am I right if I say that you...

So, in other words...

Oh, I see... you want to say that...

I get it: you mean that...

Let me see if I understand you correctly... What I think you are saying is...

If I am hearing you correctly...

Summarizing

It is quite similar to paraphrasing except that it implies a longer time and more information. It includes: to tell the key message of the story and to reformulate a longer statement into a shorter and direct form.

It can be introduced by:

“So far, we have talked about...”; “Let me summarize... you have told me that...”

Examples of summarizing:

“Let me put together all the information you have shared with me... You have said that you have one daughter and that lately you have had difficulties getting along with her... that your husband is not helpful and takes her side... that you live together with your mother-in-law in a small house... Is that right? Have I understood correctly?”

By consistently relying on “active listening”, the counsellor shows understanding and empathy for the returnee’s story and related feelings, but at the same time allows the returnee to retain the responsibility for their personal situation and reintegration.

Listening effectively to what is being said implies having an unconditional positive regard to the returnee and to what they say and an attending to and observing behaviour. What do these attitudes mean?

Unconditional positive regard

It means avoiding any attitude of judgement towards the returning migrant, not having pre-conditions for accepting them and their necessarily subjective view of the world. It means showing a sincere and neutral interest for the returnee. This means that even if the counsellor’s view radically differs from the returning migrant’s view, the counsellor respects and accepts it.

Attending and observing behaviour

It means being attentive, interested and concerned to what the migrant is sharing and to watch over what is going on during the interaction, with the aim of creating and maintaining a safe environment (not referring only to the physical one).

To help understand attending and observing in the context of counselling, it can be helpful to refer to the mnemonic SOLER:

S = Sit squarely

This means facing the returnee squarely, that is to adopt a posture that shows involvement. Sitting in an equal position: the counsellor can ask the returning migrant where he or she prefer to sit and then sit accordingly, giving the choice of sitting on a chair or on the floor. This makes the migrant feel respected and an equal of the counsellor.

O = Open posture

It is important to ask oneself which posture is culturally appropriate and shows openness and availability. In some cultures, crossing arms and legs can be signs of disrespect while an open posture can show availability and openness to what the migrant is going to say.

L = Leaning

A slight inclination of the trunk towards the migrant demonstrates interest in what is being said. Nevertheless, leaning too forward or assuming that posture too soon might be intimidating. Leaning back, on the contrary, could indicate a lack of interest, boredom.

E = Eye contact

It is important to look at the migrant while he or she is talking. This does not mean staring at the migrant but to make frequent and gentle eye contact. Nevertheless, it is highly important to be aware of cultural differences: in some cultures, eye contact is inappropriate. At the beginning of the interview, it is better not to make frequent eye contact so as to let the person get used to it. As the counselling interview goes on it is possible to increase eye contact to demonstrate full interest.

R = Relax

While interviewing the migrant, it is important to stay naturally relaxed. This helps the interviewee to get relaxed and become more focused on the topics under discussion.

Barriers to effective communication

Effective communication is also facilitated by knowing what NOT to do. These are some barriers to communication:

1. Order, command, pretend:

- You have to do what I say!

- Stop talking!

- Tell me everything about...

2. Warn or threaten

- If you do not do this, you will face bad consequences...

- You had better engage yourself...

3. Judging or criticizing

- You should have not done this...

- You had better do this...

- If you had been more careful, you would not have made this mistake...

4. Providing unsolicited advice (even if the intention is helpful and positive)

- If I were you, I would do it this way.

- This is better: choose it!

5. Disputing or challenging or putting into doubt the returnee’s choices:

- Did you really do that?

- Why did you decide to leave?

and:

- Overcomplicated, unfamiliar and technical terms.

- Emotional barriers and taboos: some migrants may find it difficult to express their emotions and may consider some topics completely “off-limits” or taboo, such as politics, religion, disabilities (mental and physical), and any opinion that may be seen as unpopular.

- Lack of attention, interest, distractions.

- Differences in perception and viewpoint.

- Physical disabilities such as hearing problems or speech difficulties.

- Physical barriers to non-verbal communication. Not being able to see the gestures, posture and general body language can make communication less effective.

- Language differences and the difficulty in understanding unfamiliar accents.

- Expectations and prejudices, which may lead to false assumptions or stereotyping. People often hear what they expect to hear rather than what is actually said and jump to incorrect conclusions.

- Cultural differences. The norms of social interaction vary greatly in different cultures, as do the way in which emotions are expressed. For example, the concept of personal space varies between cultures and between different social settings.

NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS AND TIPS

Body language. Often, it is possible to notice the changes in expression on another person’s face. Similarly, the returnee can see the expressions on the face of the reintegration counsellor and observe the tensions in their body language. This can be a sign of positive or negative attending. The counsellor needs to be aware of their body as a source of non-verbal communication.

Another fundamental non-verbal skill to implement while counselling the returnee is “silence”

Silence gives the returnee a chance to reflect on things. It offers room for reflection but it must be active, always involving interest. From the returnee’s side, it may occasionally indicate embarrassment or resentment. Most people feel uncomfortable with silences and tend to chip in with the first thing that comes to mind, which is usually irrelevant. This must be avoided. Leave pauses, even at the beginning of the counselling interview before the returnee has spoken. If they stop talking, but the counsellor feels they have not really finished, it is important to tolerate the silence. The returnee may be thinking through something important. After a while, the counsellor can say something like, “you seem to be thinking hard”; this will let them know that the counsellor is with them and can facilitate the dialogue.

Remember to show presence in the dialogue while listening by:

Giving positive non-verbal feedback. Facial expression is a clear indicator of thoughts and mood. It is important to be conscious of one’s body language. Rolling eyes, slumping shoulders, excessive fidgeting or sternness of face all show detachment from the conversation. It is good to look at the person who is talking, smile and listen with interest.

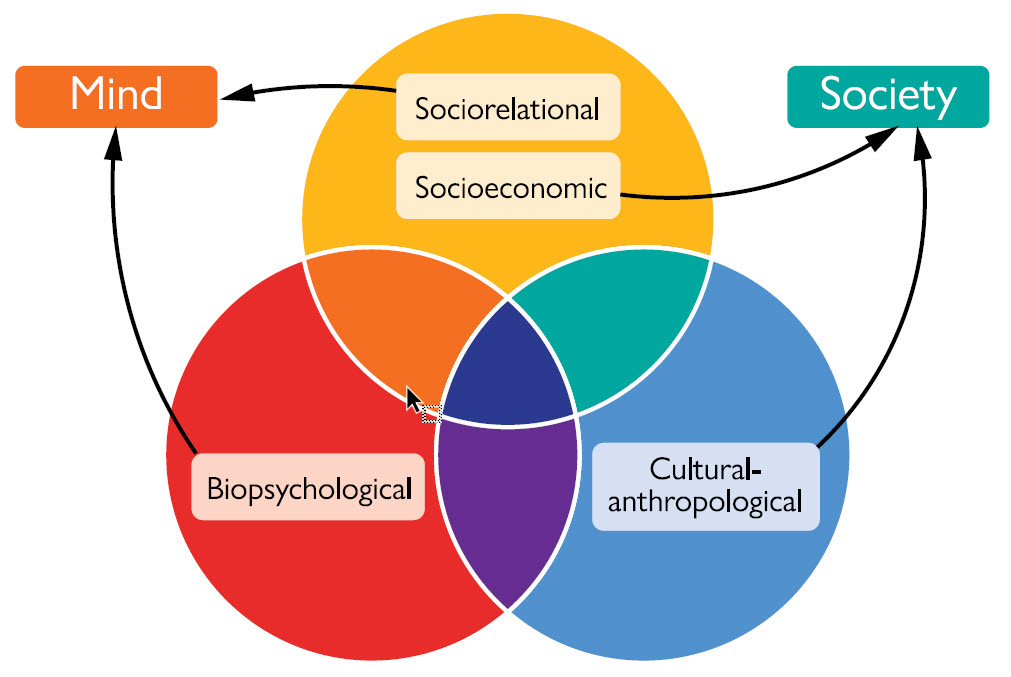

The adjective psychosocial defines the interrelation between “mind” and “society”. In the migration field, this covers three underlying and interconnected dimensions: the biopsychological, the socioeconomic or sociorelational and the cultural-anthropological ones.

Figure A.2: Paradigm of psychosocial approach83

The three factors are equally important, interdependent and mutually influencing.

The sociorelational or socioeconomic factor consists of two complementary aspects: the sociorelational brings up the quality of relations – family, friends, colleagues, peers, foreigners, enemies and others. The socioeconomic aspect has to do with the availability of and the access to resources, such as, for example, the health-care system and information technology. This factor focuses on the interactions and the interdependences between the individual and the group.

The biopsychological factor encompasses all biological and psychological factors characterizing the human being: behaviour, health, thoughts, emotions, feelings. It refers as well to the interconnectedness between the body and the mind and to the mutual influence of biology on psychological functioning and mental processes. Emotions, feelings, physical and mental health, physical and psychological vulnerabilities, stress and stress-reactions, coping mechanisms, resilience, and so on: all pertain to this factor.

The cultural-anthropological factor encompasses culture and anthropology. “Culture” is defined as “a system of shared beliefs, values, customs, behaviours, and artifacts that the members of a society use to cope with their world and with one another, and that are transmitted from generation to generation through learning”.84 Anthropology, as complementary to culture, deals with the origins, the development and the history of human beings. It studies similarities and differences within and between societies, beliefs and behaviours of groups, including rituals and traditions correlated to specific cultures. Both these are interiorized to varying degrees by individuals. In brief, the cultural-anthropological factor considers the cultural differences among individuals, how cultures are formed and how human experiences and interactions shape the world.

The three factors influence each other, and, from a psychosocial perspective, it is possible to correctly analyse and understand every aspect of the migration phenomenon when considering their mutual implications. It is possible to scrutinize any human event from within each factor: it is important to be aware that the other two factors influence any taken perspective.

How return influences the interrelation of psychosocial factors

The paradigm presented above is used to frame the psychosocial complexity of a return migration, factor by factor and in the interrelation among factors, in particular when the migration project has not led to the desired outcome. At the individual level, referring to the psychosocial model, the main reactions are:

Biophysical level

-

Fatigue, exhaustion, physical trauma

Migrants can be exposed to violence, torture, detention, exploitative work conditions that can bring different traumas and to a general state of exhaustion, exacerbated by the stress reactions. -

Infectious and non-communicable diseases

Migrants who return may have been subject to sexual and gender-based violence, exposed to contagion of different disorders and may have had a limited access to health services. -

Disabilities

As a result of violence, tortures and abuse, migrants can suffer from physical and cognitive impairment, dramatically affecting their daily functioning. -

Addiction

As a coping mechanism to the hardships of migration, some migrants can become addicted to alcohol or drugs.

Psychological level

-

Shame

Mostly determined by the perceived failure of the migration project. The returnee is persuaded that they have come back ‘empty-handed’ and have lost face. In other cases, shame might be due to traumatic events within the migration process, like violence, abuse, torture, detention. -

Guilt

The returnee might feel guilty because he or she has not been able to make good use of the economic, psychological and social investment that family, friends and community had made to allow him or her to leave. This can be aggravated by the loss of friends and relatives back home or the time spent abroad. -

Anxiety

The return migration itself is a source of anxiety with the high level of unpredictability about the future. -

Frustration

It is the consequence of the perception of having been rejected, but also of having difficulties in finding a job, creating a livelihood, being accepted by the community.

-

Sadness

Sadness comes from the failure of the migration project, the rejection in the host country and the possible rejection in the community of origin, the loss of life partners and of identity. -

Disorientation

The returnee has changed during the time spent abroad and the country of origin has changed as well. This makes them feel disoriented upon return, affecting their adjustment. -

Sense of inferiority

The returnee may feel inferior to those left behind who did not migrate. -

Self-perception of being a failure

The returnee has failed their migration projects and can blame themselves for this failure. -

Emotional instability

It is in the form of ups-and-downs: even a little success can make the returnee feel well but a small setback can make them feel not understood and lonely. -

Sense of loss

This is connected with identity crisis. Upon return, the migrant feels that the personal, social identity they had developed while abroad may not be acknowledged in the country of origin, while the old self may be lost to a certain extent. -

Feelings of hopelessness and helplessness

These feelings are connected with a loss of confidence in one’s capacity to manage events and with the belief that no event will be positive. As a result, returning migrants might not be able to mobilize energy and be proactive. -

Fear

Returning migrants can permanently feel in danger, whether the threat is real or not. This can be the result of past traumatic events, such as violence, torture or detention. -

Anger

Angry feelings can be directed towards oneself, the country of migration, the return actors and agents and relatives and friends, as a reaction to stress and due to the feeling of having been rejected or being the victim of injustice. -

Loneliness

It is a common feeling mostly connected to the perception of not being understood by family, friends and the community upon return. Loneliness has probably also accompanied the returnee during the time spent abroad. -

Low self-esteem and self-confidence

The returnee may have a negative opinion of themselves because many of their expectations have not been fulfilled and the fear of not succeeding again when it comes to reintegration in the country of origin makes them feel unvalued. The returnee may feel that they cannot succeed in any new life project. -

Focus on the past or the future rather than on the present

The present represents a challenge and sometimes a threat for the returnee. They may be more focused on the past, both because negative past experiences and events keep them stuck or because the past is in a way more manageable in comparison with the ongoing dynamic present. The returnee may focus on the future as a sort of escape from a challenging present.

Sociorelational level

-

Risk of social stigmatization

The decision to return can be stigmatized by the family and the community in the country of origin. However, this might not be the case when the migrant comes back voluntarily to invest what he or she acquired and earned abroad. -

Being perceived as a failure

The returnee is perceived or can feel they are being perceived as a failure in that they have not fulfilled the expectations of family, friends, community members who have invested money, hope, admiration and other tangible and intangible resources in their time abroad. -

Being perceived as a problem or a burden

The returnee can be seen as a mouth to feed, especially upon immediate return because of an initial lack of livelihood. In particular, if the returnee has a health condition the cost of care and the carers themselves represent an additional burden. -

Difficulty to reintegrate in the family

The family may have invested tangible and intangible resources in the migration project of their relative and upon their return may have difficulty in welcoming them back. -

Isolation from others and feelings of not being understood

Social withdrawal is a common reaction for the returnee who thinks that their present situation (and maybe even the initial decision to leave) is not or will not be understood. This is even more true for migrants who have been forced to return. Additionally, it is important to note that some returnees do not want to get in touch with or even inform their communities of origin of their return. Isolation is a leading factor for depression and can trigger a vicious cycle where the returnee does not receive any support because they remain distant from help of any kind. -

Lack of trust

The fear of not being accepted and understood may determine the lack of trust towards family, friends and community. The returnee may think that nobody is willing to support their reintegration and is most likely relying on rumours and assumptions.

Socioeconomic level

-

Poverty and financial issues

The returnee often comes back “empty-handed” from a financial point of view. They can have debts to repay and a family to support. -

Difficulty in finding a job

The economic situation of the country of origin may reduce the possibility of finding a job or of creating an income-generating activity, which may have been the reason for leaving in the first place. -

Debts

The returnee may come back with a burden of debts that they are unable to repay. They may have debts with relatives, friends or other members of the community.

Cultural-anthropological level

-

Cultural belonging

This is challenged depending on the duration of the stay abroad. The returnee has gone through a process of assimilation in the host country, learning habits, rituals and traditions. Upon return they may have difficulty in perceiving themselves as belonging to a country and to a community that may have changed or that they perceive as changed. -

Changes in the country

The country of origin as the returnee knew it may have changed in terms of norms, habits, social roles. -

Transferability of what has been learned abroad

The cultural changes, even very slight ones, in terms of norms, habits, social roles as they have been learnt abroad might be not applicable in the country of origin. -

Changes in behaviour and previous habits

Depending on the time spent abroad, the returnee has gained different habits, attitudes, behaviours and in general a different worldview. They might have difficulty in adapting again to a different dietary regime, a different pace of life and to ways of thinking that might differ much from those that they had been used to.

As previously described, these issues are interrelated. For instance, the returnee may feel ashamed because they cannot repay debts and this is a cause of social stigmatization that may make them feel lonely, excluded and without support. Alternatively, the returnee may come back with a health condition and this is a burden for the family that has to pay for their treatments, making them feel frustrated and lost. This interrelation of factors is further explained in the box below, with a very practical example.

Using the psychosocial approach paradigm to understand a returnee’s needs

“A male returnee has just arrived at the airport. He is tired because he hasn’t slept for two nights. He had to spend two days at the airport of the transit country with hundreds of other returning migrants, all cramped in a restricted area. He is Muslim. In the last two days he has had very little food. He feels ashamed and fearful about asking for food, because he does not know the rules, he does not want to be perceived as someone who begs, and he does not have any money with him in case one needs to pay for the food they may give.”

This example shows how the three factors or dimensions are interconnected: the man is hungry (biological) and ashamed (psychological) about asking for food; he has no money to buy it (socioeconomic); and he is fearful and reluctant because he does not know how to behave in this situation that is new to him (cultural- anthropological) and he does not want to be perceived as a beggar (sociorelational and cultural). In this situation, to provide help, one can prioritize the needs: the man needs food (biological), but he also needs to be reassured psychologically, have the rules explained to him and food should be provided in a way that does not embarrass him in front of his peers, and can be culturally accepted. When interacting with a returnee, the reintegration case manager should not only consider the collected information that pertain to one dimension per se, but always look at their implications with the other two dimensions. On these grounds, it is possible to design and implement sustainable reintegration programmes.

83 Schininà, G. The paradigm of a psychosocial approach in Livelihood Interventions as Psychosocial Interventions (online video 2016).

84 Bates D.G. and F. Plog, Cultural Anthropology. Third Edition. McGraw-Hill (New York, 1976).

Especially during the first encounter with the case manager, returnees may be stressed to varying degrees. Their stress can be a result of their past experiences, of their negative perception about returning, of their anxieties about the future, or they may be anxious and distressed about the counselling session itself, an important milestone in their return. It is part of the case manager’s task to provide a first-line emotional support when they observe people who are distressed.

The table A.1 below highlights some of the manifestations of distress:

Table A.1: Manifestations of distress

| Physical | Emotional | Behavioural | Cognitive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shaking | Being tearful | Poor self-care/ hygiene | Confusion |

| Fidgeting | Sighing frequently | Being on guard | Forgetfulness |

| Tapping fingers/heels | Low mood | Fast/slow rate of talking | Inability to concentrate |

| Sweating | Feeling hopeless, guilty, ashamed | Frequent swallowing, rubbing palms on clothes | Irrelevant answers to questions / difficulty finding the right words |

| Extreme fatigue | Fear | Difficulty doing the correct action | Seeing only the negative |

| Dizziness and breathing difficulties | Irritability and outbursts of anger | Restlessness | Slowed thinking |

What to do: emotional support

First, it is important to stay calm. Ask the returnee in distress if they need a break. Offer a glass of water or a practical comfort. Small talk in this situation can be helpful in reducing tensions: talk about generic topics, such as the weather, current news, hobbies.

“It is warm (or cold) here..., right?” This helps the person to get back to present reality and to detach from his or her thoughts.

“What do you like to do when you want to rest?” This helps the person to think about something that they like.

“Do you like music (dancing, sport)?” It is important to focus the question on something pleasant.

If the returning migrant is particularly stressed and shows evident signs of suffering, immediate help can be provided in the form of Psychological First Aid (PFA).

Psychological First Aid

This is a support tool aiming to help any human being, adult, adolescent or even child, who has recently gone through one or more stressful events or a prolonged stressful period. It has been developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), the War Trauma Foundation (WTF) and World Vision International (WVI) and it can be offered also by non-professionals.85

The reason for offering Psychological First Aid (PFA) comes from the evidence that people can better recover when they:

- Feel safe, connected to others, calm and hopeful;

- Have access to social, physical and emotional support;

- Regain a sense of control by being able to help themselves.

However, not every migrant who experiences a stressful event or prolonged stressful period needs or wants PFA. It is important not to force help on those who do not want it, but it must be made easily available to those who may want support.

Moreover, there are returnees who require a more specialized care than PFA. In this case, the person in need must be referred to medical or specialized psychological care. Who are they? They are returnees who:

- Attempt, or announce they have attempted, suicide, or are self-harming;

- Are particularly violent against others;

- Have reached the point where they can’t remember very simple facts of their life (such as their name), or can’t attend to basic routines (waking up, eating): this can be checked with the migrant;

- Report having recently been a victim of rape, torture, personal violence, trafficking or witnessing tragic events;

- Report being drug users;

- Report existing psychiatric conditions, especially if they did not have access to drugs for a prolongedperiod of time.

PFA can be offered during the stressful event or period, immediately afterwards or even after some time, whenever it is possible.

Regarding the context and place where PFA can be offered, it must guarantee the case manager’s and the returnee’s safety and security. Ideally, it should be provided in a place where confidentiality and a certain intimacy can be preserved.

Providing PFA responsibly means:

- Respecting safety, dignity and rights.

- Adapting what you do to take account of the person’s culture.

- Being aware of other emergency response measures.

- Looking after yourself.

Before providing PFA please, consider the following ethical norms:

| DOs | DON’Ts |

|---|---|

|

|

Relaxation exercises

It is possible to propose one of the exercises described below that have the purpose of quickly calming down the distressed person. Alternatively, if nothing seems to work to reduce the distress, the reintegration case manager can propose to stop the session and put it off to a later date, or provide PFA.

If the person feels detached from reality, help to make contact with:

- Themselves (feeling feet on the floor, tapping hands on lap);

- Their surroundings (by noticing things around them);

- Their breath (focusing on breath and breathing slowly).

One of the following exercises to relax in the short term and reconnect with the reality of “here and now” can be proposed.

Deep breathing

Preparations:

Ask the person to sit back on the chair or, if possible, ask them to lie down on their back on a sofa, on the floor on a mattress. What is important is that their shoulders, head, and neck are supported.

With a calm and warm tone, give these instructions:

(please note that in the following instructions the sign “...” means 3-second pause)

“If you feel safe, close your eyes, otherwise look at the wall in front of you (or the ceiling if lying on the back). Now, take a few breaths and focus on breathing...

Breathe in... and breathe out.... Follow the rhythm of my voice... Breathe in... and breathe out... (do not rush and try to slow down the person’s breathing as you go on)...

Now, breathe in through your nose... Let your belly fill with air...

Breathe out through your mouth... Feel your belly empty...

Now place one hand on your belly and the other hand on your chest...

As you breathe in, feel your belly rise... As you breathe out, feel your belly lower... The hand on your belly should move more than the one that’s on your chest...

Now, take three more full, deep breaths... Breathe fully into your belly as it rises and falls with your breath... Now while you breathe in, imagine the air entering your body and bringing peace and calm... Try to feel it in all your body...

And now breathe out... and while you are doing it, imagine that the air takes away all your tensions... Breathe in and breathe out...”

Repeat for five minutes or more, until you see that the person actually calms down.

To finish the exercise, give these last instructions:

“And now breathe normally... focus on your relaxed body... on the (arm) chair... and now on the room... try to visualise the room... and all the objects in the room and then you and me in the room... And now, when you feel that it is the right moment for you, slowly open your eyes... and stretch your arms and your body...”

Do it yourself to show the person how to do it and invite the person to do the same.

Should the exercise have the opposite of its intended effect, do not insist, and stop. Try another exercise.

Downward counting

It is a simple and effective exercise, based on breathing and counting. Ask the person to sit or to lie comfortably with arms and legs supported by the armchair or the floor.

Now, count each inhale and exhale, starting at 10, until you reach 1. You can say:

“Let’s count and breathe like this:

10 – inhale

9 – exhale

8 – inhale

7 – exhale

6 – inhale

5 – exhale

4 – inhale

3 – exhale

2 – inhale

1 – exhale

And now let’s repeat it...”

Repeat as many times as you feel necessary to calm the person, provided that it does not have the opposite effect.

Remember that through breathing, it is possible to indirectly control heart rate, by controlling the length and depth of the breaths themselves. Adding the technique of counting backwards alleviates the psychological effect of giving the mind a difficult task to concentrate on, essentially drawing the attention away from whatever makes you stressed and towards the internal processes taking place inside your body.

Focused imagery: The safe place

Ask the returnee to sit back on the chair (better an armchair where back, head and arms are supported). Ask them to take a couple of minutes to focus on breathing, ask them to close their eyes (if it does not create discomfort or anxiety), and to become aware of any tension in their body, and let that tension go with each out-breath.

Then, give them the following instructions:

- “Imagine a place where you can feel calm, peaceful and safe. It may be a place you’ve been to before, somewhere you’ve dreamed about going to, somewhere you’ve seen a picture of, or just a peaceful place you can create in your mind’s eye.

- Look around you in that place: notice the colors and shapes.

- Now notice the sounds that are around you, or perhaps the silence. Sounds far away and those nearer to you. Those that are more hearable and those that are more subtle.

- Think about any smells you notice there.

- Then focus on any skin sensations – the earth beneath you or whatever is supporting you in that place, the temperature, and the movement of air, anything else you can touch.

- Notice the pleasant physical sensations in your body while you enjoy this safe place.

- Now while you are in your peaceful and safe place, you might choose to give it a name, whether one word or a phrase that you can use to bring that image back, any time you need to.

- You can choose to linger there a while, just enjoying the peacefulness and serenity. You can leave whenever you want to, just by opening your eyes and being aware of where you are now and bringing yourself back to alertness in the “here and now”.

- Now that you have opened your eyes, take a moment to reawaken completely. Continue to breathe smoothly and rhythmically. Remember that your safe place is available to you whenever you need to go there.”

Show empathy with active listening, using reassuring words and non-verbal gestures. Remember that migrants who have gone through highly stressful and even traumatic events are afraid that they might go crazy and that nobody is able to understand them. They need someone who does not think they are “wrong.”

85 WHO, WTF and WFI Psychological First Aid (Geneva, 2011).

The case manager should have been informed by the counsellors in the host country about any diagnosed mental health condition of a returnee. This allows the case manager to get prepared to meet the returnee and provide assistance if necessary. If possible, the family should be involved from the returnee’s arrival. While waiting for the actual arrival, the case manager should verify the level of awareness of the family regarding the returnee’s mental health condition and, if necessary, provide them with basic information and practical management tips. If it is not possible to involve the family after arrival, the case manager should meet the returnee individually at the airport or at the port of entrance in the country. The case manager should invite the returnee to a separate quiet place, have them sit down and ask about the journey and the current state of their health (“How was the journey? How do you feel?”). The case manager should check with the returnee about any information concerning their mental health condition that has been drawn up by the host country.

The case manager can ask:

CM: “My colleagues that you met in [the host country] tell me that you have been having some mental health challenges recently. This makes your life difficult, right?”

This question has the purpose of verifying if the returnee is aware of their disorder.

If the answer is positive, this first counselling session can focus on developing a support plan, with immediate actions in response to basic needs:

CM. “Does your family know that you have come back?”

If yes, contact the family, asking the returnee whom he or she trusts more.

If no, explore the reason for not informing the family of their arrival and offer support.

CM. “Do you have a place to stay?”

If no, provide a temporary place for shelter and board.

CM. “Do you have a mobile telephone?”

If yes, take down the phone number. If no, provide them with a mobile phone.

If the answer is negative, this would mean either that the mental condition is severe and denied or that it has been misdiagnosed. It is not up to the case manager to ascertain the coherence between the information received and the actual state of the returnee. In this case, before working out any support plan and setting a calendar of meetings, it is recommended to refer the returnee to a psychiatrist, if available, to a medical doctor or to a psychologist.

CM. “Are you taking any medication for your disorder? What medication?”

The purpose here is to verify the returnee’s awareness of the disorder and check if the previously recorded medication matches with the that reported by the returnee, who should be travelling with a certificate.

If the answer is positive, it is important to verify with the returnee if the quantity of the medication they have with them is sufficient until the medical follow-up has been scheduled. If it is not, an urgent referral is needed. The continuity of care is essential for returnees with a mental disorder.

If the answer is negative, a referral to the mental health specialist is recommended regardless.

CM. “Do you have your medication with you? Do you take it regularly?”

The purpose here is to verify the compliance with the medical prescription. This informs the case manager about the resources of the returnee, their strengths and about the urgency for medical follow-up.

If the answer is positive, it is useful to praise the returnee and remind them how important it is to take medication regularly.

If the answer is negative, it is important to check the reasons and give some tips for compliance (“You can use an alarm clock as a reminder. You can set an alarm on your phone.”) In this case, a referral is required.

Already at this stage, the case manager should reassure the returnee with a mental health condition about the availability of health services in the country that can provide support.

After providing first-line emotional support, and taking into account the stress of the journey, the case manager should schedule an appointment with the returnee in the office of the organization. It is very important at this stage to obtain the returnee’s phone number AND that of a family member or, always with the consent of the returnee, of a friend.

As suggested earlier, the returnee may see no need to meet the case manager again. This may be a consequence of the disorder. The case manager should gently motivate them to seek help.

As stated before however, people with the above-mentioned conditions may need to be immediately referred if:

- They are particularly aggressive;

- They have made reference to an attempt at suicide or that they have the intention of making an attempt;

- They do not remember very simple facts about their life (such as their name) or suggest that they can’t attend to basic routines (waking up, eating, caring for personal hygiene and so on);

- They report having recently been victims of rape, torture, personal violence, trafficking or having witnessed tragic events;

- They indicate they may be drug users and in particular if they have not had access to drugs for a prolonged period of time;

- They report having existing psychiatric conditions or behave in such a way that any dialogue becomes impossible or makes the case manager feel uncomfortable, very stressed, anguished;

- They report not having or having finished the medication they should be taking.

Case managers should always be aware of their limits and not try to do everything by themselves. For people in need of a more specialized support, a referral to a mental health specialist is necessary. The case manager should explain as simply as possible the reason for the referral and the kind of support the returnee should receive, whilst also asking for the opinion of the returnees (the stigma around mental health issues should always be kept in mind).

Regardless of the statistics and the diagnosis, special attention has to be given to any migrant who show signs of mental suffering. Case managers can play an important role in stabilizing or reducing the emotional suffering of the returnees. All the communication techniques described in the previous paragraphs together with the basic knowledge of signs and symptoms of the mental disorders are useful in creating a climate of safety and trust and preparing the returnee with a mental disorder for an assisted reintegration.

As a reminder, it is recommended that the case manager, regardless of the specific disorder, always checks with the returnee:

-

If they have their medication on them (if the case managers doubt the returnee’s compliance with the prescriptions it is suggested that the family be asked to assist).

-

If the family is aware of the disorder and ready to welcome and support their relative.

-

That they and their family are reassured.

If possible, awareness sessions about mental disorders and how to give support to returnees with mental disorders should be organized for the caregivers.

E.1 Mental disorders

WHO estimates that 1 to 3 per cent of any population is affected by a severe mental disorder and around 10 per cent by a mild or moderate mental disorder. Without indulging in more clinical considerations that are beyond the scope of this Handbook, severe mental disorders are those that affect, to a great extent, the functioning of an individual, and are more likely to be chronic, while mild to moderate mental disorders do not disrupt the functioning of affected individuals to the same level, in the sense that most of the time the affected person continues with his or her life, and are likely to be overcome with time and support. The same disorder, like depression, can be mild, moderate or severe according to its degree, duration and scale of the symptoms, while other disorders like psychotic disorder are severe by definition. Research on the mental health of migrants is inconclusive as to whether migrants are more likely to develop mental disorders than non-migrant populations. The most recent systematic reviews of the most reliable studies basically conclude that there are no major differences, apart for one condition, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), that is higher in refugees86 and victims of trafficking.87 Other studies confirm a higher prevalence of psychotic disorders and depression, especially in refugees. These differences, however, even if statistically significant are not high in absolute proportions. In addition, very few studies exist on the mental health of returning migrants and their results are also inconclusive. All in all, returning migrants, although subject to several stressors, can be in need of psychosocial support, but are not likely to develop a mental disorder. In principle, one could expect among returning migrants the same proportion of severe mental disorders as other populations (2–3%) and a higher prevalence of mild to moderate mental disorders that are likely to be mitigated by time and by social and psychosocial support.

In addition, among those who return through the humanitarian return programme, such as from migrant detention centres in Libya, experiences of violence, torture, sexual violence and severe threat and exploitation are more recurrent than in other migrants, and can bring a higher prevalence of mental disorders.88

Finally, detention for administrative reasons is associated with an increase in mental disorders and this should be taken into account when dealing with returnees who have been detained.

To conclude, there is no possible generalization, and whether a returnee is vulnerable to a mental disorder depends on the unique combination of personal history, existing vulnerabilities, stressors faced during the migration period and the return and access to services throughout the migration cycle.

Among those who return voluntarily, according to information recorded by IOM, based on the analysis of most recurrent mental conditions among returnees from the Netherlands, the most common forms of mental disorders are depressive disorder, psychotic disorder and PTSD.

In the case of assisted voluntary return, based on IOM rules and regulations and identified best practices from other partners, like governments, governmental and non-governmental organizations, other UN Agencies, the return should take place only if:

- The migrant has been deemed to take an informed and competent decision.89

- The trip and the return do not put the migrant’s life at risk in relation to their mental illness.

- Continuity of care can be granted.

Therefore, if the return takes place, it is in principle necessary that the migrant is able to take decisions and to function to an extent, and that a referral system for their condition exists and has been already identified in the country.

Returnees with a mental disorder are not to be limited to their disorder only. They are also individuals with their sets of needs that transcend the illness, resources and plans and as such they need to be counselled about their reintegration. Therefore, acquiring a basic knowledge of the three identified most common mental disorders allows the case manager to better understand the behaviours migrants with such conditions may show during counselling, and communicate accordingly.

As a note of caution, it is not the case manager’s responsibility to try to identify mental disorders in beneficiaries. This would actually qualify as bad practice because mental disorders are determined by a constellation of symptoms, their scale and duration, and their interactions. Understanding the difference between a series of symptoms and a mental disorder without a clinical interview is a bad practice that can lead to stigmatization, over-referral and overall would change the relations between the case manager and the returnee during counselling. This manual gives indications about when the case manager needs to refer the person to a mental health professional or offer the referral as an option. In all other cases, the case manager should abstain from trying to diagnose. The indications below are tips for communicating with migrants who have been diagnosed with a mental disorder either pre-departure or postarrival by a professional before the counselling session takes place.

The following section will cover recommendations on recognizing, and working with migrants who suffer from depressive disorder, psychotic disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

E.2 Depressive disorder

A depressive disorder is a mental illness characterized by low mood, aversion to activity and general deep suffering. It affects the mind and the body. It differs from sadness, which is a normal part of everyday life and is much less severe. Depressive disorder, also named ‘depression’, affects the way the person feels and thinks about himself or herself and about things, the way he or she eats, sleeps and behaves. Low self-esteem, loss of interest in normally enjoyable activities, low energy and general pain without a clear cause are often elements of the depressive disorder. It is the most common mental disorder in the general population and often becomes chronic, interferes with normal daily life, and causes pain and suffering to patients and their families as well.

Manifestations of Depressive Disorders

The depressive disorder affects, as said, the mind and the body, meaning that it has both psychological and physical manifestations. The most common are listed in the table below:

Table A.2: Psychological and physical manifestations of mental ill health

| Psychological manifestations of the disorder | Physical manifestations of the disorder |

|---|---|

| Sadness and depressed mood | Fatigue or loss of energy |

| Lack of interest or pleasure in all, or almost, all activities | Sleep disturbance |

| Reduced concentration, attention and memory | Diminished appetite and weight loss |

| Reduced self-esteem and self-confidence | Psychomotor retardation or agitation |

| Ideas of unworthiness, uselessness or guilt | FHeadaches |

| Hopelessness and pessimistic views of the future | Muscle and joints pain |

Most commonly, a returnee with depressive disorder reports physical symptoms, like tiredness, headaches and body pain. The case manager, who has been previously informed of the diagnosis, does not have to investigate the psychological or physical symptoms, but he or she must be aware that behind those symptoms there is a psychological condition. It is important to bear in mind that certain negative manifestations are normal: what makes them part of a mental disorder is their combination, which can be assessed only through a clinical interview. In order to adapt the counselling setting, the communication and the behaviour accordingly, some tips are given here about the different manifestations of the disorder.

Psychological manifestations

Sadness and depressed mood

It might not be very clear at first impression. Some depressed people deny that they are sad or depressed and may say they are alright. Often, they report only physical problems. Others may be so depressed that they have few complaints and stay quiet.

The counselling room can easily remain silent with the returnee clearly in a state of unhappiness. Nevertheless, the case manager, who is aware of this manifestation of the disorder, must not get worried and not try to force the depressed returnee to feel differently. It can be counterproductive and harmful. The case manager can speak in a comforting way, with a touch of energy and optimism, adjusting the conversation and its duration around the capacity of the returnee to listen, understand, respond and react. They will avoid asking the returnee to repeat their most traumatic stories, if it is not necessary. Additionally, they will preferably not address topics that engender depressive thoughts, such as issues of loss in general, the death of someone in particular, the risk of becoming sick, the migrant’s predicament or how the returnee with depressive disorder might harm themselves.

They can suggest the returnee choose the seating, offer practical comfort like water, ask from time to time how the returnee feels, and if anything can be done to help.

It is of paramount importance to have an empathetic attitude and not a sympathetic one (see empathy vs sympathy).

Lack of interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities

The case manager has to consider that a depressed returnee is so worried about themselves and feel so guilty that it might be useless to make a reintegration plan on the grounds of the activities that the returnee (or their family) remember as enjoyable before the disorder developed. What is useful at this stage is to acknowledge the difficulty, listen carefully and illustrate the available reintegration options, especially those related to the care of the disorder. This is the only interest that at this stage the depressed returnee can cultivate. It is possible to gently encourage the undertaking of any simple activities, without forcing the returnee towards once enjoyable activities.

Reduced concentration, attention and memory

The mental functioning of a depressed person is limited because much of their mind is busy with health worries, feelings of guilt, and uselessness. The case manager has to take into account this limitation and avoid discussing complex topics, asking too many questions, abstract reasoning and being surprised if any recently imparted information is not retained by the returnee. The case manager will have to repeat information, instructions and directions more than once. This does not imply a cognitive impairment but simply that their mental processing of information takes longer. The counselling has to be focused on basic current needs: what has to be shared is the willingness to help find a concrete solution to reduce the effects of the disorder. This is what matters most for the returnee at this stage.

Reduced self-esteem and self-confidence

The returnee with a depressed disorder feels guilty for their condition: this dramatically lowers their self-esteem and consequently any confidence in the possibility that their personal resources can be of any benefit for their reintegration. Despite this, it is not the case manager’s task to work on the returnee’s inner feelings and change their perceptions. Nevertheless the case manager can encourage the returnee, praising any efforts made towards reintegration. In working out the reintegration plan, the task manager can involve, if possible and with the consent of the returnee, the family. The family members, after receiving basic information on the disorder, can help to create a context of safety and security, which is fundamental, beside the psychological support and any medication, to start a process of recovery.

Ideas of unworthiness, uselessness or guilt

The returnee with depressive disorder clings to their self-limiting beliefs of being the only person responsible for their situation. This makes them feel stuck in a jam of regrets, recriminations and self-accusations. Again, the case manager, who is aware of this typical characteristic of the disorder, does not have to challenge the returnee’s beliefs but show that they care, acknowledges their predicament, acts as a support and works for creating a context in which recovery is possible.

Hopelessness and pessimistic views on the future

The case manager should avoid working out ambitious or unattainable reintegration plans, which would probably fail. What matters most at this stage is to acknowledge the returnee’s views and refer them to a mental health professional.

Physical manifestations

Fatigue or loss of energy

The case manager has to take into account this most common symptom of the depressive disorder and adjust the duration of the counselling interview according to the capacity of the returnee to remain seated, and to listen, understand and react. The returnee may look annoyed and listless: this appearance is just the consequence of the lack of energy. The duration of the counselling interview has therefore likely to be more limited than usual and possibly agreed with the returnee. It is essential to adapt to the returnee’s current needs and possibilities and not to force the returnee to adapt to the counselling. The case manager from time to time can check with the returnee whether it is possible to go on or if it is better to stop and continue during a subsequent meeting.

Sleep disturbance

This typical manifestation of the disorder does not only mean that the returnee with depressive disorder does not sleep or has difficulty sleeping. It can mean the opposite as well: they could come to counselling sleepy and might fall asleep while speaking. Of course, the returnee cannot be blamed for this behaviour. The case manager, who is aware of this, will adapt the duration of the counselling to the actual capacity of the returnee to listen, to understand and react accordingly. Frequent breaks have to be proposed and, as an alternative, multiple shorter sessions. It is important to always check with the returnee and, whenever relevant, their family if the doctor is informed of the sleep disturbance. The case manager can remind the returnee of the importance of complying with any medical prescription.

Diminished appetite and weight loss

The case manager should be aware that weight loss can be due to malnutrition or a physical illness and that the opposite can be true as well: weight gain and increased appetite.

Psychomotor retardation or agitation

The case manager might notice that the returnee with depressive disorder moves slowly and shows uncertainty undertaking simple actions (such as taking a glass of water, standing up from the chair, entering or leaving the room) or, conversely, being agitated. If it is the case, the case manager will offer their direct support, helping the returnee to sit down, to stand up and to move inside the premises of the organization. They will work on a reintegration plan accordingly.

Headaches and muscle and joint pain

These are common physical symptoms among depressed people. The case manager might notice in the returnee muscle contractions, difficulty staying seated and grimaces of pain. They should accommodate the returnee by suggesting they choose the seating and offering practical comfort and time breaks.

Should the case manager notice in the returnee any sudden change of mood, an aggressive behaviour regardless of focus, or should the returnee share any suicidal thoughts, an immediate referral to the medical doctor has to be made.

It is important to reiterate that the case manager’s attitude and their way of talking have an important influence on the counselled returnee. This influence can be positive or negative. It is positive when the disorder is acknowledged, respected, treated with dignity and not minimized. It is negative whenever direct or indirect actions are designed to force a mood change. A person with a depressive disorder thinks that their mood and situation will never change: it is important to remember that this belief is one of the symptoms of the illness.

Communicating with migrants with depressive disorder

People with depressive disorder often feel very lonely, even when there are other people around. It is important to lessen the isolation of a depressed person but not to force socialization. This is the reason for involving the family and the community in the support of the affected returnee.

Severely depressed people feel “wrong” and they can respond negatively to anything being said to them. It is important not to get discouraged or to take replies personally when the affected migrants are unfriendly, aggressive or withdrawn.

In order to be helpful, it is not necessary to understand what a migrant with depressive disorder is going through: any attempt to show understanding might sound insincere. It is important to remember that a depressive disorder can reduce the capacity to be able to formulate words and phrases, so it is not uncommon to find oneself in a one-way conversation.

Should the migrant with depressive disorder talk of suicidal thoughts, or the case manager believes that the migrant has suicidal thoughts, it is necessary to refer them immediately to a psychiatrist or to a medical doctor.

Case managers can use some tips when talking with a depressed person:

• First of all, it is essential to acknowledge the disorder, whenever known and not to minimize it.

“I know that you are facing difficulties and I know that it is tough. It is not your fault. Is there anything that I can do for you?”

• Make the person feel comfortable talking about her or his feelings.

“If you feel like talking with me, I am happy to listen and think about how I might be able to help you.”

It is essential to use active listening techniques, but in particular to formulate short and concrete sentences.

-

It is recommended to explain that there are multiple solutions, such as medication, psychological support and psychotherapy, and to further explain elements of the treatment:

“The doctor will help you and will give you some medication that will make you feel better.” - Give the person hope that this condition will change.

“Although you might not believe me, I am confident that your suffering will get better.”

When talking to a migrant with depressive disorder, some remarks can be counterproductive and should be avoided:

-

“Everyone has bad patches...”

-

“Cheer up!” or “Just smile!”

-

“Stop feeling sorry for yourself!”

-

“What you need is to be more active, find something to do or a friend!”

-

“Remember: life is beautiful and you are alive!”

-

“We are always responsible for what happens to us.”

All the comments above are likely to just frustrate a returnee with depressive disorder because they show a lack of knowledge about depression. Many case managers fall back on words like these because they have no direct or indirect experience of depression. It is essential not to try to fix the problem but it is always useful to remind the person with depressive disorder the importance of medication and compliance with therapy.

Psychological counselling

As already stated, only trained professionals can provide psychological counselling which, in the case of depressive disorder, can be helpful if the manifestations are mild or moderate and a psychosocial stressor (a clear cause) is present.

If psychologists or counsellors are not available, the reintegration case manager should refer the returnee to the medical doctor. It is very helpful for a depressed person to see that people are supportive.

Psychosocial support at individual level

Psychosocial support interventions can help the returning migrant to:

-

Be aware of his or her problem;

-

Be aware of the opportunities and the risks of reintegration;

-

Reduce the sense of guilt;

-

Reduce the sense that what is happening to them feels “wrong”;

-

Increase self esteem;

-

Reduce the feeling of stigma;

-

Integrate into the community.

Psychosocial support at family level

The family, if possible, has to be involved. The case manager can help the family to:

-

Recognize the state of the illness of their relative.

-

Identify a member of the family that the returning migrant trusts more and who could take good care of them.

-

Suggest that the family does not force the person to do anything but invite him or her to try to resume once enjoyable activities.

-

Identify small social activities but without forcing participation.

-

Discuss the importance of medication and compliance with it.

-

Find occupational or vocational training and employment in a protected environment.

Psychosocial support at community level

It is important to help the community understand the disorder with basic information. This process can be undertaken through community leaders and the involvement of the family. A group briefing co-conducted by the case manager and the community leader (and, if available, a medical doctor) in the presence of the family but not necessarily of the migrant with the disorder, would represent good practice. It would target the stigma and create a collective supportive environment around the individual concerned.

E.3 Psychotic disorders

Psychotic disorders are mental states characterized by loss of contact with reality. The person is conscious and awake, but it is as if they live in a different reality, which only they are aware of. The person is not dreaming and firmly believes in what they affirm.

Examples:

The person connects things that are not usually connected and jumps from one thing to another, such as in the following example:

-

Case manager: “Can you tell me your name?”

- Person: “My name? My name is Akram. Akram is married. Are you married? Being married is good. Do you want to marry me?”

Starting a sentence that goes in a certain direction, but even before the sentence is finished the person is already going in another direction:

-

Case manager: “Where do you live?’

-

Person: “I live in the village of Monday. Monday. Monday is blue. Friday is black.”

In the following example, the sentence is gibberish. The person uses words that he makes up himself. The words have no meaning for anyone listening.

-

Case manager: “What is your name?”

-

Person: “Tra. Bi bi bi. Ta ta ta”

The causes for psychotic disorders are unknown, but there are many risk factors for developing them. Some risk factors are:

| Biological | Psychological | Social |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

None of these factors, alone, however is sufficient to explain why a person develops a psychotic disorder. Most likely, multiple factors are involved.

As said, the person is conscious, but experiences hallucinations, delusions and thought disorders, meaning that they believe something exists when it does not. Additional manifestations can be present as well, like withdrawal, agitation or disorganized behaviour.

Manifestations of the psychotic disorder

Hallucinations

When a person hallucinates, they are seeing or hearing things that are not real, but are convinced that they are real. Examples:

-

Hearing things that no one else can hear;

-

Voices talking to them, commenting on them;

-

Voices in their head;

-

Strange sounds or music coming from unknown places;

-

Seeing things or persons that no one else can see.

The person sometimes keeps silent about these things because they realize that other people do not believe them. Often, however, they react to the hallucinations as if they were real. For example, they may talk or shout in response to someone that is not actually there.

The case manager, when confronted with verbal behaviours of this kind, should keep calm and act naturally, and should not contradict the returnee. They should listen actively. The aim here is to avoid an emotional escalation and an acute crisis. In case of aggressive behaviour, verbal or physical, or of self-harming acts, the case manager should ask for help and refer the returnee immediately to a psychiatrist, perhaps even with the support of the police.

Delusions

Delusions are false thoughts that no one in the person’s environment shares. The person with delusions is convinced that their ideas are the truth, even if there are signs that prove that they are mistaken. The person persists with these ideas.

This symptom refers to the content of the thoughts (what the person is thinking). Examples:

-

Believing that people are trying to kill them, even when there is no evidence in support of this notion.

-

Believing that everyone in the street, on the radio and television or on the internet, is talking about them.

-

Being convinced that persons have implanted radio equipment in their body so that someone else can keep track of their actions.

-

Being certain that they have a lethal disorder, without clinical evidence.

-

Thinking that they are very famous or rich, when this is known not to be true.

The case manager has to act naturally and gently reassure the returnee who, at this stage, is probably agitated and stressed. The case manager can calmly show a different, safe reality, assuring the returnee that nobody has bad intentions and that no one is following them from the inside.

Thought disorders

These are characterized by the person talking in such a way that other people cannot understand what they are saying or cannot follow their line of reasoning. There seems to be no logic behind their words. Sometimes the person may even talk pure nonsense, using made-up words or incomplete sentences.

Because of the psychotic disorder, the person can be convinced that their thoughts do not emanate from their own mind but are literally ‘put in their head’ by other people. Alternatively, they might think that their thoughts are “stolen” by other people and removed from their head to be broadcast, for example, on the radio or to be read by other people. These are rare examples but if they occur one can be almost certain that the individual is suffering from a severe psychosis called schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia. A long-term mental disorder of a type involving a breakdown in the relation between thought, emotion, and behaviour, leading to faulty perception, inappropriate actions and feelings, withdrawal from reality and personal relationships into fantasy and delusion, and a sense of mental fragmentation (Oxford University Press, 2018).

It is recommended not to contradict the returnee, but to listen actively, reiterating that the only reason for being present is to help them.

Severely affecting the mind, psychotic disorders also manifest behavioural symptoms, such as the following:

Withdrawal, agitation, disorganized behaviour

The psychotic behaviour is chaotic and disorganized. There is no apparent reason in the person’s acts. Examples:

-

Collecting, or keeping trash or things that have no value;

-

Wearing clothes in a strange or inappropriate way;

-

Destroying things without realizing what is happening;

-

Sitting motionless, without moving, for a very long time;

-

Talking to self and laughing suddenly (when nothing funny has happened) or smiling when recounting sad events;

-

Crying without a clear reason;

-

An impossible or unusual physical complaint such as having a snake inside the brain, or an animal in the body, or the absence of body organs;

-

Showing no emotion when something happens that would usually provoke strong emotions, for example, receiving a present or receiving bad news;

-

Showing indifference towards things that are generally important, for example, food, clothing, money;

-

Social withdrawal and neglect of usual responsibilities related to work, school, domestic or social activities.