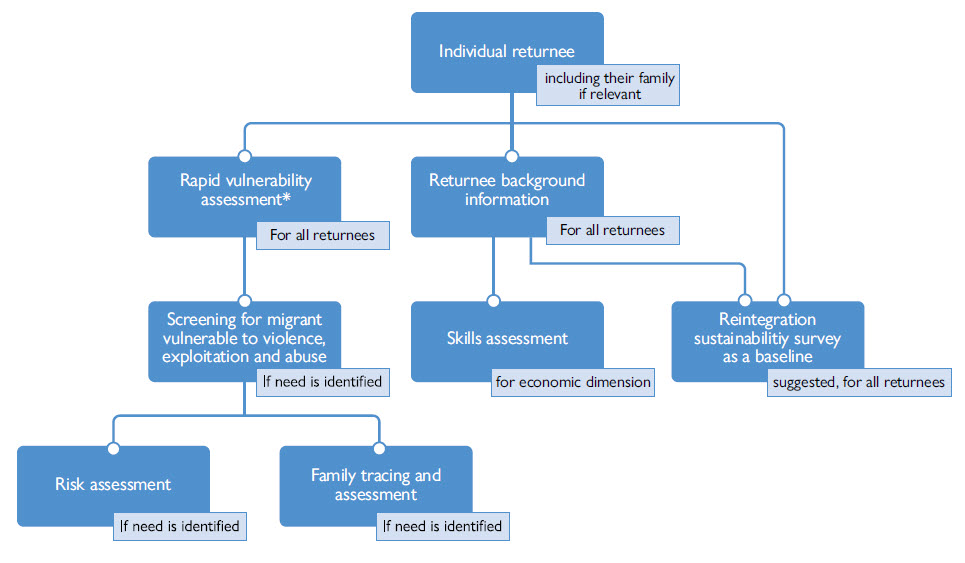

Individual assessments explore returnees’ capacities and vulnerabilities as well as their protective and risk factors. These assessments provide information to tailor each returnee’s reintegration plan and should be revisited if circumstances change. The graphic below shows which assessments should be undertaken for which returnees and when.

This chapter presents an overview of the assessments to be carried out to gather the information necessary before developing a reintegration plan:

- 2.2.1 Vulnerability assessment

- 2.2.2 Risk assessment

- 2.2.3 Family assessment

- 2.2.4 Skills assessment

- 2.2.5 Reintegration Sustainability Survey as an assessment tool

Figure 2.2: Suggested assessments to be carried out before developing a reintegration plan

* Please note that if rapid vulnerability assessment reveals potential vulnerabilities, the follow-up screenings should be carried out as soon as possible.

In order to design a reintegration plan that provides tailored assistance, assessments should be carried out as early as possible, ideally before return. Receiving information regarding the returnee prior to their return allows staff in the country of origin to arrange appropriate assistance upon arrival. After the returnee arrives in the country of origin, information provided by the host country staff should be reassessed by reintegration staff. Close coordination between staff in the host country and country of origin is crucial to support a smooth reintegration. For an example of how this is undertaken, see Case Study 2, below.

Pre-departure cooperation between IOM country offices in Afghanistan and Austria

Since 2012, IOM Afghanistan and IOM Austria have been cooperating on reintegration projects. Efficient communication, quick responsiveness and willingness to continuously adapt and improve reintegration approaches have proved to be crucial prerequisites for facilitating the reintegration process for returnees in an often-difficult context.

Solid cooperation starts from the project design phase, where both offices provide equal inputs to content and budget elaboration. To support smooth and efficient case management, standard operating procedures are shared by the offices. These hold information on all project staff as well as office details of both offices, describing roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders involved in the return and reintegration process. Together, the offices develop information materials for returnees and translate these into local languages.

During project implementation, there is continuous communication and information sharing through emails as well as regular Skype sessions; specific topics such as monitoring are discussed in webinars. IOM Afghanistan staff provide regular inputs for the pre-departure information sessions that IOM Austria arranges for returnees. This helps build trust, provides a realistic overview of opportunities and challenges upon return and helps manage returnees’ expectations.

Coordination and monitoring visits in both Afghanistan and Austria reinforce the established cooperation because they provide further understanding of the working realities, procedural requirements and pre-departure and post-arrival contexts for returnees. In addition, these visits are an opportunity for IOM staff to meet with partners and other organizations to inform and build trust. They are also a way to expand referral networks and therefore enhance the sustainability of reintegration, for example in the areas of health, or technical vocational education and training. Likewise, coordination meetings in Austria allow IOM Afghanistan’s staff to provide key stakeholders with up-to-date insights on the situation in Afghanistan.

- Build staff capacity to facilitate intercultural communication and cooperation;

- Collect returnee feedback after return to help create realistic expectations for future returnees.

2.2.1 Vulnerability assessment

All returnees should undergo a vulnerability assessment, ideally before departure and again upon arrival in the country of origin (see Step 4, above).

Individual and household-level vulnerabilities must be identified early to determine whether they could prevent participation in the reintegration process. Early identification of vulnerability also helps staff prepare appropriate protective and preventive measures and is crucial for creating an effective reintegration plan.

Definition of a migrant in a situation of vulnerability

Migrants in vulnerable situations are migrants who are unable to effectively enjoy their human rights, are at increased risk of violations and abuse, and who are thus entitled to call on a duty bearer’s heightened duty of care. Vulnerable situations that migrants face arise from diverse factors that may intersect or coexist simultaneously, influencing and exacerbating each other and also evolving or changing over time as circumstances change. Factors that generate vulnerability can cause a migrant to leave their country of origin in the first place, may occur during transit or at destination (regardless of whether the original movement was freely chosen) or may be related to a migrant’s identity or circumstances. Vulnerability in this context should therefore be understood as both situational and personal. (Adapted from IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019).

The Rapid Vulnerability Assessment screening form and the Migrant Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse screening form are tools that should be used prior to travel and again when returnees arrive in their country of origin. They will soon be available online. These assessments should be carried out by trained staff. The full screening assesses all potential sources of vulnerabilities for the individual migrant and within families.

Some vulnerabilities require direct intervention to address immediate needs before and after arrival. Adults who are found to be at risk of intimate partner or other types of violence, may need assistance with protection and safety measures. Other vulnerability factors require longer-term responses that should be included in the migrant’s reintegration plan (for example, ensuring that chronic medical conditions are attended to). The results of vulnerability assessments should be provided to staff in the country of origin prior to a migrant’s travel only if the migrant consents to this.

For more detailed information on identifying and assisting migrants in vulnerable situations, please refer to the IOM Handbook on Direct Assistance for Victims of Trafficking and IOM’s Handbook on Protection and Assistance to Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse.18

Health vulnerability considerations

A basic health assessment or, at a minimum, screening for specific health needs, should be undertaken as part of the vulnerability assessment for all returnees before departure. If needed and the migrant consents, physical assessments should follow. For migrants with health needs, case managers need to be alerted to the fact that there is a health vulnerability. There needs to be comprehensive knowledge of available health services in the country of origin to enable the development of a transition plan before a returnee travels. This helps determine, for example, if a migrant can stay on the same medication or treatment regime (especially for mental health and autoimmune disorders) in the country of origin.

In contexts where health needs (for example, diagnostics, physicians, medication) for chronic health conditions (for example asthma, renal disease, diabetes, HIV) cannot be met in the country of origin, relocation needs to be considered in collaboration with health service providers in both the host country and the country of origin. The options all involve extensive counselling and include:

- Not to return. Return should not take place if the returnee is receiving life-saving or life-prolonging treatment in the host country and he or she will be unable to receive such treatment in the country of origin. Patients may still want to return under these circumstances. However, this should not be facilitated if the absence of critical services (for example, dialysis) will result in the death of the returnee.

- Continue with return. The patient may be in a terminal stage and would rather obtain less sophisticated palliative care with their family and loved ones than stay alone in a more resourced hospital. When care in the country of origin is available, but limited, extra effort should be made to help the returnee access this care.

- Relocation to another area. This is not always possible, but should be explored if the option exists.

Guidance to case managers for these situations is complex and decisions should therefore focus on collaborating with subject matter experts, trusted colleagues and, most importantly, the returnees.

Continuity of care must be prioritized when working with migrants in vulnerable situations, especially when it comes to health needs. The returnee should be alerted to any changes in medication or treatment regimens, and these must only occur with the returnee’s full participation and consent.

2.2.2 Risk Assessment

If returnees are identified as vulnerable, case managers should carry out a risk assessment and put in place an individualized security plan. Guidance on how to do this is found in the Handbook on Protection and Assistance to Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse.

Special Consideration: Victims of Trafficking

People attempting to reintegrate into home communities after being victims of human trafficking can have special needs and considerations that need to be accounted for during reintegration. Among these is the extra support victims of trafficking may need for family reunification and rebuilding social networks. Successful reintegration may require tracing families prior to return so victims can return to their own communities. It could mean educating a victim’s family about what the returnee was subject to while away. If risks exist for social rejection or isolation due to stigma associated with human trafficking, then case managers need to call on local NGOs, local service providers or trained staff to advise how to facilitate familial acceptance. Victims of trafficking may also be in greater need of temporary housing, medical and psychological services, or special security measures if any threats exist during their return. Preparing for these extra needs in the pre-return of reintegration is crucial. The IOM Handbook on Direct Assistance for Victims of Trafficking (2007) and IOM’s Handbook on Protection and Assistance to Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse provide in-depth guidance on how to serve victims of trafficking.

2.2.3 Family assessment

Family members can play an important role in a migrant’s decision-making process. An assessment of a returnee’s family situation, especially for returnees who are considered vulnerable, can provide valuable insight into factors that could support – or hinder – the returnee’s successful reintegration. This is also called “household assessment”. For more information on this type of assessment, see the tools provided as part of the IOM Handbook on Direct Assistance for Victims of Trafficking (2007) and IOM’s Handbook on Protection and Assistance to Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse (2019).

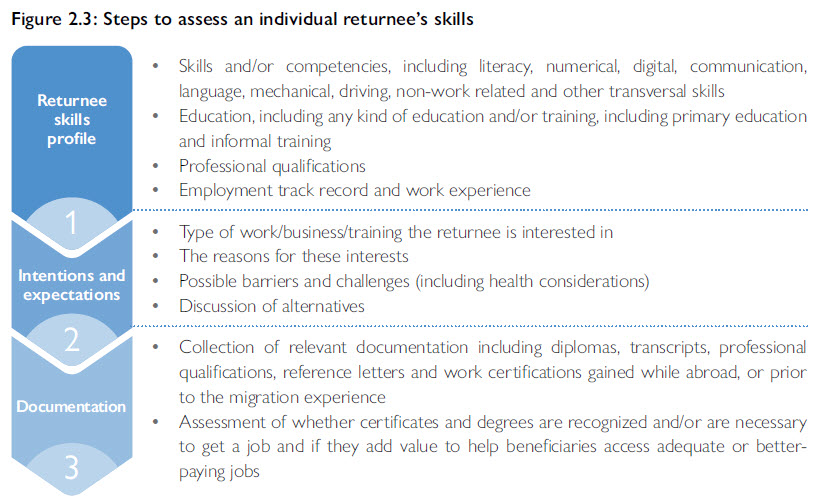

2.2.4 Skills assessment

A skills assessment should precede the development of the reintegration plan. Gathering information on a returnee’s skills, education and aspirations is important for:

- Tailoring reintegration support, especially economic assistance;

- Recognizing and addressing any potential mismatch between a returnee’s existing skills, training and the skills demand in the country of origin;

- Helping the returnee feel that reintegration assistance is building on their specific needs and strengths and that they have a chance of succeeding; and

- Creating an element of trust and encouraging ownership in the reintegration process.

The figure below outlines the steps that can be taken to assess returnees’ skills.

There are several tools available to help facilitate an individual skills’ assessment such as:

- EU Skills Profile Tool for Third-Country Nationals, intended for use by organizations offering assistance to third-country nationals for labour market integration, with a configuration feature to allow organizations to create their own tailor-made questionnaire;

- Skills Health Check (United Kingdom), which identifies skills and qualifications of jobseekers in order to help returnees steer their career plans;

- UNESCO International Standard Classification of Education.

Skills or competency tests assess beneficiaries’ specific skills irrespective of how and where they were acquired. Skills may have been gained through means that include any combination of formal or informal training and education, work or general life experience.

Case managers can refer returnees to skills’ tests if one or more of the following facilities are present in the country of origin and are willing to cooperate within the referral framework of the reintegration programme:

- Institutes for the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) provides assessment and certification that proves a person’s competency, based on occupational standards, regardless of how these competencies were acquired. RPL is important for self-employed people looking for jobs, workers seeking career progression, workers in the informal economy wanting to shift to formal jobs and practitioners wanting to enter an educational pathway. RPL is very important in the context of return migration, as it allows workers to have the skills they may have acquired abroad recognized in their country of origin.

- General skills’ testing facilities include those provided by TVET centres. Skills’ testing facilities often use several assessment methods or strategies to measure an individual’s performance, competencies and skills. They provide a range of testing methods for different occupational competencies.

- Public employment services (PES) and private employment agencies (PrEAs) are generally services that assist in matching job candidates with employers and often provide other services such as counselling and vocational guidance, job-search courses and related forms of intensified counselling for people with difficulties in finding employment. In countries where PES or PrEAs are available and provide skills’ assessments in-house, consider referrals for returnees who are already likely to possess the skills and competencies for the occupation envisaged in the reintegration plan. For returnees eligible for job placement, the skills’ assessment should directly link to the assisted job search and matching process foreseen by the PES or PrEAS.

- Employers providing on-the-job skills’ verification and training for returnees allow returnees to work on the job to demonstrate their skill level, or to practice in a limited authorized format. Depending on the specific regulatory system of the country of origin, the returnee might also be issued a provisional or conditional licence, which is made permanent once the individual’s skills have been verified during his or her on-the-job performance.

In case none of the above types of entities are present in the country of origin, the case manager should coordinate with relevant CSOs and NGOs to set up a service stream for skills’ assessments that is linked to the qualifications framework of the country of origin.

While some providers (for example, public employment services in most contexts) conduct skills’ assessments free of charge, others may charge returnees a variable fee that is dependent on the skills’ assessment provider and the range of skills and competencies assessed.

2.2.5 Reintegration Sustainability Survey as an assessment tool

One way to perform a comprehensive assessment of a returnee’s reintegration situation is to use the Reintegration Sustainability Survey scoring tool.19 This scoring system evaluates the returnee’s ability to achieve sustainable reintegration along the economic, social and psychosocial dimensions (see section 1.3 for explanation of the three dimensions).

Using the survey at the assessment phase can serve three purposes:

- It provides a standardized and holistic approach to tailoring reintegration assistance;

- It establishes a common set of indicators to create a baseline for monitoring returnees’ progress towards sustainable reintegration over time;

- It helps case managers identify returnees whose reintegration needs may be higher, because returnees with lower scores are more likely to require greater support and follow-up.

When the tool is used throughout the reintegration process, the information it gathers can be used to help answer the following question: To what extent have returnees achieved a level of sustainable reintegration in their return communities? It is important to note that using the Reintegration Sustainability Survey as an assessment tool does not replace the other assessments (above) because those should still be used to pinpoint the specific areas of intervention.

Understanding the survey results

The scoring system produces:

- A composite reintegration score measuring overall reintegration sustainability and which is therefore useful as a general baseline measure; and

- Three separate dimensional scores (economic, social and psychosocial) that measure sustainability in each dimension of reintegration and can highlight discrepancies in status and progress between these dimensions, as well as areas where further assistance might be desirable. Two migrants with a similar composite reintegration score might have very different dimensional scores, signaling different reintegration experiences and needs.

For more detailed information on using the Reintegration Sustainability Survey, including the indicators and survey tool, see Annex 4.

Results use in case management and reintegration planning

All scores are between 0–1 and case managers can use a reintegration score calculator included in the package to automatically process respondents’ answers and calculate the reintegration scores. Case managers can then adjust the intensity of case management and reintegration assistance: an intensified approach would be advisable for returnees whose composite or dimensional score falls below 0.33. If a score reaches values above 0.66, case managers can employ a hands-off approach, with lighter support for the beneficiary overall or in the specific dimension of reintegration where the returnee has achieved a high score. Understanding the reintegration needs of beneficiaries through this scoring can therefore enable case managers to allocate their efforts and services or resources where they are needed most.

Be careful when interpreting scores generated for respondents with a large percentage of answers falling under the “I don’t know/I don’t wish to answer” category. It is recommended that for all respondents who use this answer option more than seven times (more than 20% of indicators), the number of “I don’t know/I don’t wish to answer” responses should be noted alongside their reintegration scores. This will highlight that the scoring might carry a lesser degree of accuracy.

18 This Handbook is specifically concerned with a subset of vulnerable migrants: those vulnerable to violence, exploitation and abuse. Any use of the term “vulnerable migrants” for should be understood to mean migrants vulnerable to violence, exploitation and abuse.

19 The scoring system was developed on the basis of conclusions from IOM’s Mediterranean Sustainable Reintegration (MEASURE) project in 2017, funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID). The survey design was tested through qualitative and quantitative fieldwork in five key countries of origin: Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iraq, Senegal and Somalia. See more in Samuel Hall/IOM, 2017.