Working in close partnership with key actors and organizations at all levels contributes to the sustainability of reintegration programmes. It also reinforces national and local ownership of reintegration initiatives. Strategically engaging reintegration stakeholders and developing their capacities improves effectiveness of activities and promotes the continuity of reintegration interventions beyond programme implementation. Strong coordination mechanisms at the international, national and local levels are also crucial for sustainable reintegration. These structural-level interventions should be considered in all reintegration programmes, starting early in the planning phase and continuing throughout programme implementation.

To strengthen the capacities for sustainable reintegration locally and nationally, structural initiatives should reflect the needs and priorities identified by government and civil society in countries of origin. These types of interventions can include:

- Engaging and reinforcing local and national capacities to deliver reintegration-related services through technical and institutional support;

- Reinforcing the fulfilment of rights for returnees and non-migrant populations alike through quality services in such essential areas as education and training, health and well-being, psychosocial support, employment and housing;

- Increasing sustainability of reintegration interventions by fostering their ownership by local and national authorities and other stakeholders in countries of origin; and

- Strengthening policy frameworks to promote well-managed migration (see section 4.3).

Reflecting these priorities, it is important to engage with identified stakeholders through a tailored engagement approach with the aim to develop joint strategies to address reintegration needs at the individual, community and structural levels.

This chapter presents a detailed overview of essential work with reintegration stakeholders.

4.1.1 Stakeholder engagement

4.1.2 Capacity-building and strengthening

4.1.3 Establishing coordination mechanisms

4.1.1 Stakeholder engagement

Following the stakeholder mapping carried out during the design stage (see section 1.4.2) and based on the reintegration programme’s strategic objectives and the selection of relevant stakeholders, the lead reintegration organization needs to define an engagement and communications strategy for the various groups of mapped stakeholders. Engagement strategies are descriptions of how a given stakeholder is approached and how relationships are managed over time. The strategy needs to be tailored to stakeholders’ specific profiles as well as to their expected role in the programme. In particular, engaging with local authorities at an early stage is crucial, considering their in-depth knowledge of local services and their direct link to returnees and their communities.

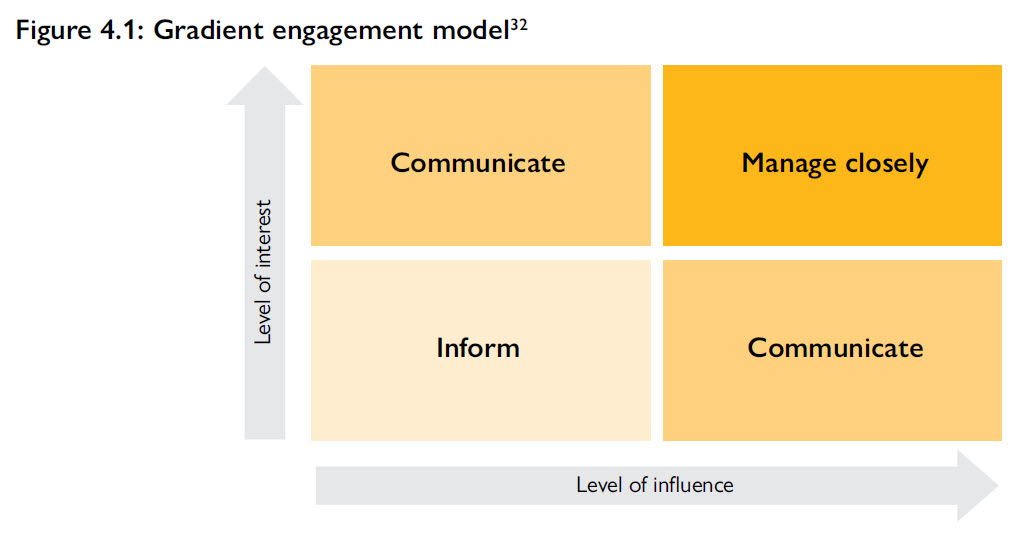

Engagement strategies can be classified into the following three categories, according to stakeholder level of interest in the reintegration programme and their level of influence over the reintegration process.

- Inform (low priority): For stakeholders with low levels of influence and little interest in the implementation of the reintegration programme and who may be interested only in obtaining information about what is happening, the lead reintegration organization should simply provide periodic information on its objectives and activities, such as through awareness-raising campaigns, publications or reports.

- Communicate (medium priority): For stakeholders with either a higher level of influence or high level of interest in reintegration programming, the lead reintegration organization should engage in two-way communication to help them value the engagement. Their targeted involvement in reintegration activities should be sought. Communication can be coordination (with partners that can provide certain reintegration services), or invitations to planning sessions (such as for community-based activities) or prioritized access to information on the reintegration programme.

- Manage closely (high priority): For stakeholders that can exert a large influence on the reintegration process and who also have a high interest in engaging with the lead reintegration organization, a tailored engagement approach should be developed. This can take the form of a memorandum of understanding, a joint local development project with a local municipality, a public-private partnership with relevant private actors, research collaboration with a local university or periodic meetings to align processes and identify synergies.

When developing stakeholder engagement plans, it is important to anticipate stakeholders’ perceptions of the reintegration programme.

An overview of different stakeholder categories and their possible functions is provided below:

Table 4.1: Stakeholder categories and their relevance and functions33

| Stakeholder | Relevance | Possible functions |

|---|---|---|

|

➔ National authorities ➔ Ministries ➔ Government agencies |

National-level authorities are primary stakeholders because they develop national policies and initiatives that provide the framework for local programmes. They are instrumental to shaping international relations with host countries, partner governments and international organizations. |

|

| Stakeholder | Relevance | Possible functions |

|---|---|---|

|

➔ Provincial and local governments ➔ Municipal stakeholders ➔ Associations of municipalities |

Local authorities are important because they can operate as an interface between different local actors and between local and national-level actors. They can also provide insight into local priorities and connect reintegration support to existing local development plans, local services and resources. In some cases, they can play a role in bilateral cooperation, through the establishment of decentralized cooperation frameworks. |

|

|

➔ Private sector |

Private sector actors are important especially for economic reintegration, because they are employers with insight into the local labour market. They often have access to diverse resources that are not always mobilized in support of reintegration, particularly financial resources and technical expertise. (See next section.) |

|

| Stakeholder | Relevance | Possible functions |

|---|---|---|

|

➔ NGOs |

NGOs are important actors, nationally and locally, because they have good local knowledge and networks and can mobilize communities and address social issues. |

|

|

➔ Diaspora organizations |

Diaspora organizations can be important because they understand migration experiences and have access to resources and cultural knowledge in both host and origin countries. They also generally have existing social networks in host and origin countries to mobilize support for reintegration. (See further in this section for more information.) |

|

|

➔ Migrant associations |

Migrant and other associations can be important because they understand the migration experience and may already be promoting reintegration, even if indirectly, through their projects. |

|

| Stakeholder | Relevance | Possible functions |

|---|---|---|

|

➔ International organizations ➔ Foreign governments ➔ Other third parties |

International organizations, donors and foreign governments can be important stakeholders because they contribute to and make recommendations for national frameworks, undertake their own assessments and programming and have access to resources and technical expertise. |

|

|

➔ Academia |

Academia can be a useful partner because academic institutions have done or can do research and analysis in the local context. They also have technical experts and existing facilities. |

|

Monitoring the outcomes of stakeholder engagement can provide insight into how to adjust the approach and engagement methods. Monitoring should build on a summary of noted stakeholder concerns, expectations and perceptions, a summary of discussions, and a list of common outputs (decisions, actions, proposals and recommendations) agreed during initial exploratory talks. A few months following the initial engagement, and after any significant changes, assess progress towards achieving these common outputs and adapt the stakeholder engagement approach when progress is insufficient.

Depending on the type of relationship envisaged with a particular entity, consider formalizing the partnership with the stakeholder. How to formalize depends on the type of stakeholder. With service providers, a lead reintegration organization generally has a long-term agreement (LTA), while partnerships with national and local authorities are generally formalized through memoranda of understanding (MOUs).

Stakeholders may have competing priorities or limited resources and as a result may not be able to engage as envisioned by the lead reintegration organization. However, this could change over time. It is therefore important to remain in contact with stakeholders, even if they are initially unable to support reintegration programming. Their interest in engagement can shift over time.

When considering which stakeholders are relevant for reintegration programmes, the potential roles of the private sector and diaspora organizations can sometimes be overlooked. However, these actors can play an important role in supporting reintegration outcomes, internationally, nationally and locally.

Private sector engagement

Private–public partnerships can generate livelihood opportunities for returnees and community members and support social integration. Private–public initiatives can include awareness-raising around returnees’ experiences, job placement, training and apprenticeships or internships.

Private sector entities can generally benefit from the reintegration of returnees. They can use returnees’ manpower and skills; they may benefit from financial incentives to hire or train returnees; and they may enjoy increased visibility of corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts.

Companies operating in a country of origin may seek specific skills’ profiles that are not present in the local population. These companies could be interested in promoting employment of prospective returnees in the country of origin, especially if these returnees have suitable skills gained in the host country. No matter the motivation for hiring returnees it is important to match the skills, needs and interests of returnees to companies’ skills’ needs and required qualifications (see also section 2.4 on developing targeted economic reintegration plans).

Beyond serving as potential employers for returnees, the private sector can have other positive contributions to reintegration programmes. For instance, the private sector can play an important role in supporting and setting up demand-oriented skills’ development programmes or by certifying skills returnees have acquired abroad. For more detail on possible activities to undertake with the private sector, see Table 4.3. Local authorities can often provide a first overview of local private actors who are already engaged in activities that are relevant to reintegration programming.

When entering into partnerships with private sector entities, check that private sector partners are genuinely interested in engaging with returnees and there is a trust relationship between the partners. To avoid a misalignment in the approach taken by a private sector entity regarding the objectives of the reintegration programme, objectives, goals and standards need to be clearly communicated to any potential partner.

Table 4.2 shows, step by step, how to develop a private sector engagement strategy.

Table 4.2: Developing a private sector engagement strategy34

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

|

➔ Determine the prevalent skills, challenges, and needs of returnees |

Building on skills' and needs' assessments and the aspirations of returnees, determine whether the focus should be job placement, vocational training, inkind support, or counselling. |

|

➔ Identify and assess existing private sector engagement strategies |

Map existing private sector engagement strategies within the organization and those of partners' and assess whether they are compatible with the objectives of the envisaged economic interventions. If there are appropriate existing strategies, work to streamline reintegration into those, rather than building separate strategies. |

|

➔ Identify relevant companies |

Identify companies that could support the reintegration of returnees by filling identified needs (such as, by providing employment, training, internships, or apprenticeships). |

|

➔ Identify existing matching mechanisms |

Identify existing international, national and local referral and matching mechanisms between jobseekers and private sector entities (public or private employment services, skills' assessments institutes, private pathways for recognition, prior learning). |

|

➔ Develop and implement a private sector engagement roadmap |

Develop a private sector engagement roadmap that reflects project priorities. Engagement can range from sensitizing private entities to the need to support returnees’ socioeconomic reintegration, to providing subsidies or incentives for including returnees (short-term wage co-financing, co-paid apprenticeships, and so forth). (See section 2.4) |

|

➔ Monitoring and evaluation |

Assess the impact of private sector engagement on the socioeconomic reintegration of beneficiaries, based on the baseline indicators. |

Some countries of origin may have local or national job matching systems, although they may not be fully functional. In case no national or local matching mechanisms exist, developing a jobseekers’ database can be considered if reintegration programme resources are sufficient. Due to the resource-intensive character of this type of intervention, partnering with other organizations or institutions and developing co-funding arrangements is encouraged.

Table 4.3 (below) provides an overview of how different types of private sector partnerships can address specific challenges of return migration.

Table 4.3: Reintegration challenges that can be addressed through private sector partnerships35

| Challenges | Relevant private sector actors | Type of initiative/partnership | Comments/examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate access of returnees to private sector jobs |

➔ Employers |

|

|

| Lack of certified skills |

➔ Employers in relevant sectors ➔ Skills' training centres |

|

|

| Resentment in communities of return |

➔ Communication sector |

|

|

Cooperation with diaspora

Diaspora in host countries are an important resource for reintegration programming and can contribute to the success of local-to-local partnerships. Diaspora communities can be bridges between origin and host countries because they generally have an understanding of the language and culture in both. At the same time, their knowledge of and emotional connection to their country of origin places them in a favourable position to invest there. To leverage the potential of diasporas abroad to further reintegration programming (and socioeconomic development more broadly) in countries of origin, the lead reintegration organization can help stakeholders in the country of origin connect to the diaspora. The lead reintegration organization can also help align diaspora initiatives with local reintegration and development priorities (see Table 4.4, below).

Table 4.4: Supporting authorities in the country of origin

| Action | Activities of the lead reintegration organization |

|---|---|

| Mapping diasporas |

➔ Help stakeholders in the country of origin conduct a comprehensive diasporamapping exercise. The model should capture diaspora demographics and socioeconomic profiles, strength and nature of ties with country of origin, past and present socioeconomic contributions and characteristics of bilateral relations between country of origin and the countries in which the diaspora live. |

| Identify priority diasporas |

➔ Support identification of priority diaspora communities in selected countries based on demographic weight, their historical and current engagement with socioeconomic development in the country of origin and the nature and strength of bilateral relations between diaspora countries and the country of origin. |

| Develop diaspora engagement strategies |

➔ Support development of strategies for country of origin on engaging effectively with prioritized diaspora group:

|

| Implement diaspora engagement strategies |

➔ Help countries of origin implement the diaspora engagement strategy by facilitating dialogue and exchange through return and reintegration offices in the host countries. |

| Monitor and evaluate diaspora engagement |

➔ Continuously monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of diaspora engagement strategies on reintegration projects and make appropriate adjustments in the engagement strategy. |

Countries of origin may not always have specific schemes or incentives in place to encourage diasporas to invest. Because investment by diaspora businesses and entrepreneurs can be a significant source of foreign investment, the lead reintegration organization could incentivize national and local authorities to develop diaspora investment models that leverage migrants’ savings for local economic development in the country of origin and in support of sustainable reintegration of returnees. Possible innovative ideas can include the legal, financial and regulatory facilitation of partnerships between diaspora business executives and returnee and other business executives in the country of origin under a clear regulatory framework. This can reduce information asymmetry, uncertainty and transaction costs and thus enhance incentives to invest.

Also, country of origin authorities can consider creating mechanisms by which national and local governments can complement the contributions of diaspora members or returnees to fund community-based local development projects. Depending on the willingness of diaspora investors to invest and on potential localbarriers to investment, the government could also consider issuing security guarantees for certain investments (such as partnerships for service provision in areas of high return; generating employment opportunities for returnees and local non-migrants) to further incentivize diaspora investments.

4.1.2 Capacity-building and strengthening

Capacity-building for reintegration programmes involves strengthening the skills, structures, processes or resources of key stakeholders so they can facilitate the sustainable reintegration of returnees. Capacity building can be targeted at any stakeholder (international, national or local) that plays a role supporting reintegration. It is best used when there are stakeholders who are motivated to support reintegration but have identified capacity gaps.

Capacity-building and strengthening can comprise the following activities, often undertaken in partnership with national and local authorities and organizations:

- Building and strengthening structures, processes, coordination mechanisms and referral mechanisms for sustainable reintegration;

- Helping national institutions analyse national indicators for monitoring reintegration, and integrating the indicators into wider migration and development-monitoring frameworks;

- Training and mentoring local and national government agencies, service providers and implementing partners to provide services to beneficiaries in a targeted, accessible and equitable manner, in line with their mandate;

- Providing funds or in-kind support for equipment, infrastructure or additional staff to support service provision or coordination;

- Improving coordination for reintegration management between international, national and local actors;

- Helping local governments develop or strengthen their ability to analyse return and reintegration issues within the wider migration and development context, and to identify and articulate priorities;

- Support local authorities to collaborate with civil society.

Capacity-building and strengthening should be integrated into all stages of the reintegration programme and should not be considered a one-off activity. National and local authorities in the country of origin should closely cooperate with the lead reintegration organization to check that existing capacity-building plans are taken into account and that existing coordination structures at various levels of government are leveraged.

(See Case study 13, below, for an example of how IOM worked with authorities in Georgia to strengthen job counselling targeted at returnees and internally displaced persons.)

Job Placement and Counselling in Georgia

Limited knowledge in countries of origin on hiring opportunities and promising sectors jeopardizes efforts to properly respond to labour market needs and hinders jobseekers’ access to employment.

In coordination with local authorities, IOM Georgia redesigned and expanded the employment support service network by opening new job placement and counselling centres (JPC) in six strategic areas where many internally displaced persons and returnees reside.

The inception phase of this work included assessing the labour market, constructing counselling centres and hiring and training local staff to work as job counsellors. Once established, the JPC started providing outreach information sessions and individual career plan development.

Outreach activities include job fairs (organized in numerous locations to increase their coverage). These fairs provide information on market needs and on available support for business creation, start-ups, vocational training, self-employment and job placement. Jobseekers can register in a database to match their profiles with employers’ needs. This database also facilitates follow-up. Furthermore, beneficiaries can go through individual needs’ assessments, after which they may be directed to vocational training opportunities or existing job vacancies.

To complement the JPCs, IOM Georgia supported national authorities’ efforts to enhance the employability of jobseekers by designing new vocational training programmes for high-demand sectors, training staff and renovating and equipping various training spaces.

The JPCs were originally managed by IOM but are now operated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Social Affairs.

- Replicate the job centres in contexts where the formal employment sector is dynamic or growing.

- Train JPC staff to interact with jobseekers and remain aware of local market dynamics, training opportunities and promising sectors.

Table 4.5, below, provides an overview of how capacity development can be integrated at different stages of the programming cycle.

Table 4.5: Integrating capacity development into reintegration programming36

| Phase | Capacity-building activities |

|---|---|

| Situation analysis |

➔ Use the situation analysis (see section 1.4.2) to undertake capacity assessments of stakeholders and identify capacity gaps; ➔ Identify local and national stakeholders that could support capacity development activities; ➔ Map existing capacity-building strategies and explore ways to mainstream reintegration-related objectives into existing initiatives, rather than creating stand-alone capacity-building programmes. |

| Strategic goals and priorities |

➔ Prioritize reintegration-related capacity gaps; ➔ Based on these gaps, develop capacity-building initiatives; ➔ When possible, align outcomes with existing national and local priorities. |

| Capacity-building strategy |

➔ Develop a capacity-building plan summarizing the results of the capacity assessment and listing all the identified priorities (see more details below) |

| Implementing the capacity development plan |

➔ Follow up on the capacity development plan and inform stakeholders of the progress; ➔ Implement the capacity-development plan. |

| Monitoring & evaluation (M&E) |

➔ Develop capacity in collecting, processing, analyzing and disseminating data on return and reintegration; ➔ Integrate into the M&E framework indicators to measure progress on the development of capacity in the area of return and reintegration. |

Building on the situation analysis and reintegration programme outcomes, the lead reintegration organization should develop a capacity-building strategy that takes into account the following questions.

- Sociopolitical context: What sociopolitical factors are challenges to implementing reintegration programming (such as community resilience, political climate and so forth)? What are the priority reintegration and migration issues?

- Institutional context: What are the institutional and policy frameworks that shape the roles of stakeholders? How do the decisions of key stakeholders affect return and reintegration policies and programming?

- Capacity context: What are the needs and capacity gaps of stakeholders? Who has the best knowledge of good reintegration practices in the country of origin? What resources do stakeholders have at their disposal to provide long-term support to the reintegration programme?

- Coordination and accountability: How can capacity-building maximize stakeholders’ capacity to utilize and benefit from existing coordination and information systems?

- Resources: What resources are available to facilitate capacity-building and sustainable reintegration support for each stakeholder?

The capacity-building strategy identifies and prioritizes evidence-based and objective-oriented activities. It effectively contributes to addressing the needs and goals of stakeholders in line with the objectives of the reintegration programme.

The strategy enables the creation of an action plan and can assist practitioners in deciding which activities will concretely contribute to the overall goals of the reintegration programme and advance the objectives of all parties.

Capacity-building can be aimed at enhancing the tangibles (physical assets, technical competencies and organizational framework) or intangibles (social skills, experience, institutional culture) of an institution or stakeholders, as shown in Table 4.6, below:

Table 4.6: Examples of capacity-building and strengthening activities

| Tangibles | Intangibles |

|---|---|

|

➔ Support the elaboration of national and local policies, strategies and programmes into which reintegration and return can be mainstreamed. ➔ Provide institution-specific or joint training courses to enhance the capacity and knowledge of civil servants, staff or managers. ➔ Where there are large numbers of returnees, support the development of inter-institutional coordination mechanisms (inter-agency agreements, MOUs, a steering committee) for relevant national and local actors involved in return and reintegration. ➔ Provide targeted economic resources and required assets or equipment where relevant for streamlining returnees into the service portfolios of existing service providers and implementing partners. ➔ Provide technical support for the revision of standard operating procedures and regulations. |

➔ Support meetings of government authorities, service providers, civil society organizations, private sector entities and other relevant actors to explore ways of improving coordination and cooperation between stakeholders and to strengthen informal ties between actors. ➔ Design and implement programmes to support social skills for staff working with returnees and to enhance social cohesion. ➔ Provide material and training to strengthen organizational values, institutional culture and staff motivation in relation to key issues of return and reintegration. |

At the subnational and local levels (such as municipality or community), implement capacity-building to generate a greater effect on reintegration and to improve service provision, including in ways that benefit the local non-migrant population. When working on local capacities for reintegration support, embrace a multi-stakeholder approach in which local authorities, private sector actors and civil society organizations are actively involved at each step of the process. Capacity-building, in this sense, can empower local authorities and other stakeholders to streamline reintegration support in their areas by i) supporting the local provision of services in areas of high return, ii) promoting decentralized cooperation, iii) applying for pertinent national and international funds and iv) strengthening coordination mechanisms among local actors and between local, national and international counterparts. (See Case study 14, below, for an example of local capacity-building in the Republic of Serbia.)

Capacity-building and reintegration management in The Republic of Serbia

Ten years after the outbreak of war in the former Yugoslavia, the Republic of Serbia encouraged its citizens abroad to return to their country. To that end, IOM supported national authorities to adapt the existing local action plans for refugees from ex-Yugoslavia and internally displaced persons to include the needs of returnees in Serbia, between 2001 and 2012.

IOM Serbia, in coordination with the Serbian Commissariat for Refugees and Migrants, needed to bridge existing action plans with local needs. Through guidance at the national level, local migration councils were set up as suitable counterparts for political dialogue at local level.

IOM Serbia therefore mentored and coached local municipalities to conduct their own needs’ assessment along with a mapping of services for housing and livelihoods. Through a consultative process with targeted local municipalities, IOM provided technical assistance to update and expand local action plans to accommodate registered returning nationals. To harmonize local measures used by different municipalities, local action plans were clustered by neighbouring municipalities and country-wide exchanges of experiences were organized.

Foster political willingness and recognition from local communities, because they can facilitate the flow of activities.

4.1.3 Establishing coordination mechanisms

An effective mechanism is required to coordinate activities of government actors and service providers, such as public and private employment services, technical and vocational education and training institutes (TVETs), business development support centres, education institutions, health-care providers, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). Strong coordination supports efficient and sustainable reintegration programming. Depending on the context and the scope of the reintegration programme, coordination mechanisms can be international, national or local.

In most contexts, some form of governmental coordination capacity is likely to already exist. However, it may be dispersed around various government agencies and offices. In some cases, the country of origin might already have a dedicated coordination mechanism for migration-related issues, including those related to return and reintegration. In this case, the aim should be to strengthen and unify the existing dispersed lines of coordination under the umbrella of one (possibly already existent) coordination mechanism.

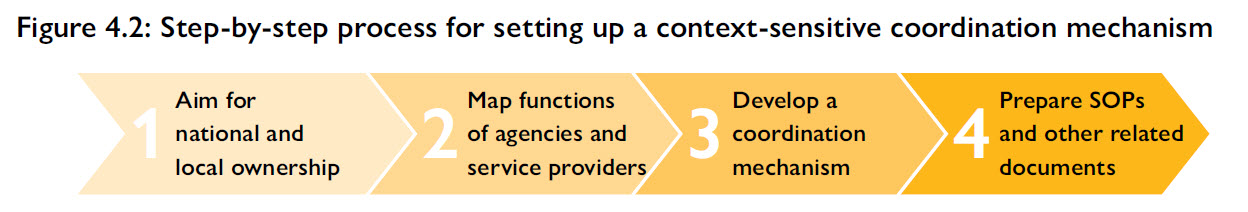

However, in some places only limited coordination mechanisms are in place or there is no coordination between relevant reintegration actors. In this case, it may be necessary to establish a new dedicated coordination structure. Key steps in designing, implementing and maintaining a dedicated coordination mechanism are outlined below.

-

Aim for national and local ownership of the process. The overall coordination of reintegration activities should be led by the government of the country of origin, to increase government ownership of reintegration and legitimize the coordination mechanism with regard to government agencies and other service providers.

In addition to national government entities, local and regional authorities are essential actors in return and reintegration. Coordination is therefore required not only between different national-level actors (horizontally) in the country of origin, but also between national, regional and local stakeholders (vertically). In some countries, there may be existing vertical government coordination mechanisms for processes such as job placement, health-care services, training and basic service provision which can be used and strengthened within a larger reintegration coordination mechanism.

-

Map the functions of agencies and service providers at local and national level. The assessment of frameworks, regulations and policies for service provision and service mapping (carried out when reintegration programmes are designed, see section 1.4.2) should be updated with information on existing coordination mechanisms and the hierarchy and relationships between different agencies and service providers. Careful analysis should be undertaken as to where institutionally the coordination mechanism should fit, whether it can be situated within existing frameworks or requires new ones.

-

Develop an adequate coordination mechanism. Building on the service-provider mapping, put in place a mechanism that facilitates the coordination of national or local stakeholders involved in return and reintegration activities. A coordination mechanism can be an inter-agency working group or an interministerial committee. The coordination mechanism should i) be formally endorsed by the government of the country of origin, ii) be chaired by the relevant local authority or national ministry in charge of return and reintegration, iii) comprise high-ranking officials from each relevant line ministry and agency,37 and iv) be supported by experts as well as representatives of international organizations and civil society.

-

Prepare standard operating procedures (SOPs) for relevant implementing partners.This should include supporting the development of SOPs, joint instructions or joint protocols for all institutions and service providers that are engaged in reintegration-related activities, from registration and assessment of beneficiaries to monitoring and evaluation.

SOPs should include:

- What and how information and data are transferred. It is important to exchange only information, including personal data, that is required for effective care and assistance. Personal privacy is of the utmost importance. The information transferred to other support organizations should be limited to details that are needed to facilitate the specific adequate care for the returnee.

- Information about how services are provided and beneficiary consent requested. The returnee should provide consent to share feedback between care services to facilitate follow-up and coordination.38

- How the first contact is arranged. Details about the first point of contact at each referring organization, including main contact person(s), times available, response times for getting called back, if required, and case data required at first contact.

- Follow-up and continuity of assistance. Partners should agree on what further assistance might be required by each organization and arrangements for post-appointment information-sharing, including, for example, in the health context, passing on information about prescriptions and treatment regimens, potential health, including mental health, risks.

- Strong documentation structures. Details of support provided by service providers should always be available and documented in a timely, accurate and secure manner. Documentation should include contact details of all actors involved, information on assessments, the assistance plan, information on the monitoring of the plan, outcomes of communications with the returnee and service providers involved in the assistance plan, feedback from the returnee and any other pertinent information.

- Cost arrangements. These should also be included in SOPs, and if relevant any agreements for joint trainings, equipment sharing and so forth.

Referral mechanisms

Having an effective referral mechanism in place is crucial for addressing the full array of potential needs returnees might have.

The lead reintegration organization cannot meet every kind of need a returnee might have, so organizations and government services need to connect to one another to be able to help migrants in a comprehensive way. A referral mechanism for returnees can be defined as a formal or informal process of cooperation between multiple stakeholders to provide assistance and protection services to returning migrants.

Referral mechanisms typically include a mapping of services available for returnees. This will inform the development of some type of memorandum of understanding that lays out what the various partners do, as well as standard operating procedures that describe how these connections – or referrals – are made, including how data will be collected, managed and protected. The organizations (or agencies, providers and so on) work together, in effect creating an efficient and accountable network that acts as one ‘deliverer’ of services. However, it is important to note that a referral mechanism is not a one-off document, but rather the process of working together through various steps of the assistance process.

Referral mechanisms can be local, such as a local case worker referring a client to health screening at a clinic or to a local housing cooperative, or to a jobseekers’ consortium that is active in the area. They can also be national, for example connecting returnees with national or international organizations that can provide support or protection through their national network. And they can be international, country-to-country or multilateral, with countries having formal ways to refer migrants to the services of another country or for assessment in, or passing information, to that country.

For more information on developing and implementing referral mechanisms (including sample forms), please refer to the IOM Guidance on Referral Mechanisms for the Protection and Assistance of Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse and Victims of Trafficking (2019).

Module 2 provides guidance to case managers on selecting appropriate services for individual returnees and making referrals within a coordination mechanism.

National reintegration SOPs in Côte d’Ivoire

Since 2016, Côte d’Ivoire has seen large number of its nationals returning, especially from Libya and the Niger. This has put a strain on national structures and capacities, which did not previously have established structures in place to assist these returnees. As such, the Government of Côte d’Ivoire has been working closely with IOM to set up specific SOPs and coordination mechanisms to be able to assist a larger number of returnees.

Following a mapping of local and national partners, under the leadership of the Ministry of African Integration and Ivorians Abroad (MIAIE), a Case Management Committee (“Comité de Gestion des Cas”) involving key ministries, government departments and a CSO was established. Through this committee, the Government of Côte d’Ivoire adapted IOM’s “Framework Standard Operating Procedures for Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Assistance” for the national context by drafting a national plan on return and reintegration.

These SOPs are now being reviewed at ministerial level for adoption by a council of Ministers. The plan foresees an assistance-sharing approach for which each partner allots assistance to returning migrants according to their budgets, capacity and function.

The committee also manages cases and selects partners for reintegration. Furthermore, some gaps identified during the mapping are being addressed. For example, a reception centre is being renovated where returnees will receive first-hand assistance including counselling, emergency housing, livelihoods’ kits and petty cash. Training sessions on migrant child protection for social service officers are also being provided to prepare them to respond to the needs of a high number of returnee migrant children.

Similar mechanisms are being established across 26 African countries in the Sahel and Lake Chad, the Horn of Africa and North Africa through the EU-IOM External Actions to Support Migrant Protection and Reintegration of Returnees programme.

- Capitalize on each partner’s expertise, strength and geographical coverage to strengthen the system.

- Ensure that the coordination mechanisms established are accompanied by resources to build capacity.

32 Adapted from: G. De la Mata. Do You Know Your Stakeholders? Tool to Undertake a Stakeholder Analysis (2014).

33 Sources: Joint Migration Development Initiative (JDMI), Module 1: Managing the Link Between Migration and Local Development, Module 2: Establishing Partnerships, Cooperation and Dialogue on M&D, in My JMDI e-Toolbox on Migration and Local Development, Geneva, 2015; Samuel Hall/IOM, 2017.

34 Adapted from: Samuel Hall/IOM, 2017 and IOM, Reintegration - Effective Approaches (Geneva, 2015).

35 Adapted from: JMDI, 2015b; IOM, Reintegration - Effective Approaches (Geneva, 2015).

36 Source: IOM, 2010.

37 Depending on the scope and planned activities of the reintegration programme, relevant line ministries can include the Ministry of Interior for activities related to registration and documentation; Ministry of Labour for PES and TVET; Ministry of Health for health services; Ministry of Education for educational reintegration, and so forth.

38 In some specific situations, referrals by a family member or an organization without the migrant’s consent are justified when his/her life is at risk, such as when there is a high risk of suicide, or when the migrant is suffering from a mental disability and is not able to give his/her consent. These last options can be determined only by a mental health professional.

- 4.1/4.3

- Next