Key Messages

Target audience

Introduction

A child rights approach to reintegration addresses the child’s immediate and long-term needs within the framework of the UNCRC. These needs include nurturing relationships, social, emotional and life skills, and access to education, health, economic and community participation of the family or caregiving unit as the child develops. A multiplicity of factors including personal characteristics and aspects of the migration experience impact reintegration at the individual level. Resilience informs individual factors within the context of the ecology that surrounds a child, their developmental stage, and their individual capacities and skills, in relation to the adversity associated with their migration journey. Potential protective and risk factors can contribute to or undermine a child’s resilience and progress towards sustainable reintegration. Risk factors include exposure to child trafficking, child labour, aggravated smuggling and other forms of exploitation.

Key factors affecting the reintegration of children include:

- The support and acceptance of family, community and peer groups. A failed migration journey following substantial investment by the family and community often results in stigma or reprisals for returnee children and families.

- Access to educational and training opportunities.

- Access to health services including mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) services.

- Child specific considerations such as age, sex, gender, identity, sexual orientation, ability or other individual characteristics of the child. For instance, older children require appropriate and viable economic reintegration assistance options.

Chapter 6.2 examines the case management approach to responding to the needs of returning children and families. It highlights the importance of the social service workforce and provides guidance on the various steps of the case management process which should be adapted to the local context.

Establishing and strengthening case management in various contexts

The case management system should be embedded in a functioning national child protection system. The primary objective of a child protection case management system is to ensure that children receive quality protection services in an organized, efficient, and effective manner, in line with their needs. A social service worker, or group of workers – professional or paraprofessional – undertake key tasks associated with the case management process, from assessment of children’s needs to organizing and coordinating appropriate services, as well as the monitoring and evaluation of service delivery. Some key resources required for effective case management include Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and tools, trained workers, safeguards for handling personal data, transport, telephone or other communication devices, a place to hold meetings, and a system of documentation including use of technology. Building on formal mechanisms while strengthening the technical and financial capacity of informal and community actors, addressing the security and individual risks to the child, mapping of available services, developing referral mechanisms, and awareness-raising about available service provision can address potential gaps while case management systems are being established and strengthened. Civil society organizations and multisectoral coordination supplements case management to ensure timely reintegration assistance for vulnerable migrant or returnee children.

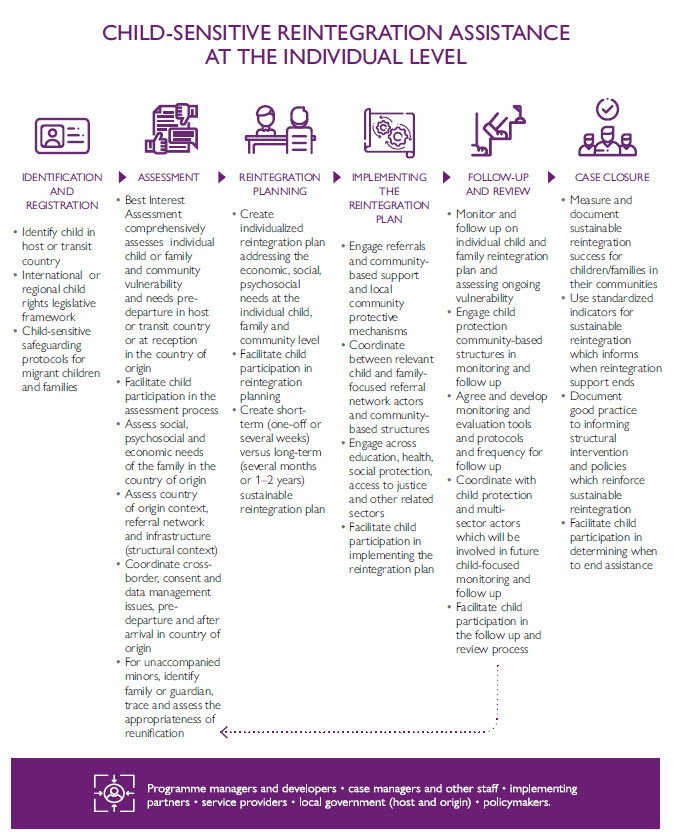

The diagram below outlines the case management steps proposed by the Inter Agency Guidelines for Case Management and Child Protection and aligns them with the reintegration assistance process at the individual level described in Module 2. The steps outlined below are interconnected and each one may require a return to an earlier stage in the process while steps may be repeated several times before a case is closed.64 There is no specified duration within which each step should be completed. However, national authorities and relevant stakeholders can develop guidance to set appropriate time limits.

6.2.1 Introduction to Case Management

Case management is a way of organizing and carrying out work to address an individual child’s (and their family’s) needs in an appropriate, systematic and timely manner, through direct support or referrals.65 The case management process commences with identification and registration and ends with the implementation of a sustainable solution. It involves working with children and families to establish reintegration goals, creating reintegration plans to achieve those goals, providing services to meet needs identified in assessments, monitoring progress toward achievement of the reintegration plans, and closing cases when goals have been achieved.

While a well-developed social service workforce is critical to ensuring coordinated, integrated and tailored reintegration assistance across all sectors, the responsibility for child protection case management is often shared among various sectors and agencies such as social welfare, education, health, security and justice and involves actions taken by both formal and non-formal or community actors. Social service workers tasked with case management contribute to sustainable reintegration by providing pre-departure or postarrival information and connecting returnee children and families to available services at the community, local and national level. Reintegration assistance should be anchored within a comprehensive child protection and welfare system that meets both national and international obligations towards children irrespective of their nationality or immigration status.

6.2.1.1 Competencies for the social service workforce, case managers or workers

The following competencies and areas of training are recommended for the social service workforce

supporting reintegration assistance for returnee children.

- Good understanding of child development. Case managers working with children should have a thorough understanding of the age of the child or children in relation to the stage of development. This means being educated on the physical, intellectual, emotional, social and language development of children from early childhood through adolescence.

- Child-sensitive psychosocial assessment. Case managers should have training or experience conducting comprehensive psychosocial assessments. This includes the ability to assess the intersection between stage of development, health, education, ability or disability, family, environment, community and other risk and protective factors and personal psychological traits and psychosocial influences as they impact on the child’s level of resilience.

- Informed consent with children and caregivers. Case managers should understand issues regarding consent, including the process of gaining informed consent from the parent, caregiver or guardian as well as being able to engage the child using child-friendly communication to facilitate receiving informed consent from the child in accordance with their developmental stage.

- Red flags, signs and symptoms of child abuse and distress. Case managers working with children should have knowledge of the different signs and presentations of abuse, neglect, distress and exploitation in children according to their developmental stage and cultural or social context. As an extension of this, case managers should understand these signs and symptoms enough to know when and at what level follow-up or referral for additional services is needed for the child.

- Ethics and appropriate boundaries with children. Case managers should understand the complexity of issues related to ethics and boundaries when working with children. This includes knowing how to establish professional boundaries but to also be able to appropriately engage and earn the trust of children, abiding by a code of conduct and applicable child safeguarding policy, managing the limits of confidentiality when sharing information with guardians, caregivers or other professionals and fostering meaningful child participation while always keeping the best interests of the child in mind.

6.2.1.2 Facilitating meaningful child participation during case planning

Case counselling

Engagement and establishing trust are a priority for encouraging meaningful child participation. The quality of the social worker or case manager’s engagement and ability to establish trust facilitates all other steps and objectives for the counselling session. The counselling session can then facilitate:66

- Establishing a helping relationship;

- Helping children to tell their story from their own point of view;

- Attentive listening to children;

- Helping children to make informed decisions;

- Helping children build on and recognize their strengths.

6.2.1.3 Techniques to advance case counselling and child participation

Engagement of children in the case management and counselling process can be facilitated by employing different techniques depending on the child’s age, developmental stage and individual history and circumstances.67

- Counselling modality. Counselling modality types include individual, group or family counselling. Each modality has its benefits depending on the focus of the objectives of the work the case manager hopes to do with the child or young person. Individual counselling provides one-on-one attention and is specific to the needs of the individual child. Group counselling can help address social isolation and normalize the child’s experience. Family counselling can help engage family members in supporting the child while exploring family dynamics which may impact the sustainability of reintegration support.

- Use of creative activities. The use of creative activities can help children engage in the case management and counselling process. Activities can include the use of play, art, music, drama, storytelling and other creative activities which allow a child to express themselves and their wishes beyond the use of language. Case managers can also create child-friendly content and explain material which might otherwise be overly complex for a child to understand by using the above creative techniques to present ideas, information or concepts.

- “Joining” with children. It is important to take time at the beginning of the case management relationship and first counselling session to build a good relationship with the child. This can include greeting the child and talking about something that is easy or light-hearted, allowing the child to guide the case manager to discuss what is important and comfortable for them. This technique is called “joining” because the case manager is joining the child where they are rather than imposing the case manager’s agenda. Joining can look like a fun, creative activity for a child under 12 or speaking about a young person’s likes and dislikes for an older child.

6.2.2 Case management steps

6.2.2.1 Identification and Registration

Returnee children and families can be identified by immigration actors, child protection or social welfare

authorities and community members in a variety of ways:

- In transit or at border points while they seek to access a State territory;

- In a host country having recently arrived;

- Following longer-term stay in a host country having fallen out of regular status or remained undocumented;

- Once they return to their countries of origin and communities.

| Protecting the rights of the child during identification and registration |

UASC |

Children in |

|---|---|---|

| Child friendly and gender sensitive. Consider the child’s specific vulnerabilities including whether the child is unaccompanied or separated, their age, gender, disability status and their resilience, taking into consideration the ecology surrounding the child. Facilitate referral to direct services including urgent medical assistance. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Registration. Conduct initial interviews to collect the child’s biodata and social history in an age-appropriate and gender-sensitive manner, in a language the child understands and by professionally qualified personnel.68 Data collected begins the case documentation process and should be kept confidential and allow for easy retrieval on a need to know basis. The child and family (or guardian in the case of unaccompanied children) should give informed consent to registration. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Context specific. Conduct or access a country of origin assessment broken down by region or municipality cross referencing child specific vulnerabilities. The assessment conducted in the country of origin should inform the social, economic, political, security and institutional conditions at the local and national level. Stakeholder and service provision mapping are important aspects of such assessments to be further explored in the reintegration planning phase. They require frequent updating on the capacity, needs, willingness, potential for multisectoral partnerships, and the criteria for service provision at the local and national level. | ✓ | ✓ |

6.2.2.2 Assessment for the individual needs of the child and family

The assessment explores the child’s and family’s protection needs, vulnerabilities or risk factors, resilience capacities and resources. (See figure 2.2, Module 2 for suggested assessments to be carried out before developing a reintegration plan). The Best Interests Procedure (BIP) consisting of a Best Interests Assessment (BIA), process planning and a Best Interests Determination (BID) is the standard for the assessment and general case management for migrant and returnee children seeking sustainable solutions. The BIA is an assessment tool for the protection of individual children. The BIA can take place at various points throughout the BIP to assess any actions taken that may have a direct impact on the child’s best interests. The BIP should be part of a comprehensive child protection system with support from international and civil society partners where national capacity to conduct the BIP is not yet fully operational. Part 6, IOM Handbook on Protection and Assistance for Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse provides further information on how the best interests principle can be applied in practice.

| Protecting the rights of the child during the assessment |

UASC |

Children in |

|---|---|---|

|

Identifying individual vulnerabilities. Conduct a BIA when unaccompanied or separated children are identified, or children within families that exhibit risk factors such as abuse, violence or exploitation. |

✓ | ✓ |

| Referral to child protection authorities. Refer unaccompanied children identified in transit, at border points, in a host country or in their countries of origin to child protection and welfare authorities. | ✓ | |

| Access to a qualified guardian. Provide access to a qualified or trained guardian and legal representative with whom the child can build a trusting relationship, have an overview of the child’s activities and provide consent on education and social life decisions. The guardian should be appointed through an administrative or judicial process. | ✓ | |

| Safe and accessible. Ensure access to safe accommodation, education and health services including pre-departure planning and consider family circumstances and social relationships.69 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Appropriate care provision. Ensure appropriate accommodation separate from adult migrants or returnees, for unaccompanied and separated migrant children. Prioritize familybased alternative care and prohibit child immigration detention in the host country. | ✓ | |

| Initiate family tracing as soon as possible. For unaccompanied and separated migrant children, the family should immediately be traced and assessed to reunify, if it is established to be in the child’s best interest.70 | ✓ | |

| Best Interests Determination. Return has long-term implications for the child’s survival and well-being and must be informed by a BID. The BIA leads to the BID in situations where a child is in need of a sustainable solution. It should take place in the host country pre-return but should also inform the long-term care for returnee children identified in their country of origin. A BID case manager should convene the social worker, guardian, legal representative, child psychologist and other relevant child protection actors and stakeholders in a case planning meeting that contributes to informing a sustainable solution. It should be documented, consider immediate, interim and long-term measures and involve the child’s participation. |

✓ | ✓ |

| Facilitate child participation and understanding. Where the child disagrees with a BID that concludes that return is the best sustainable solution, the child must receive adequate support to understand the situation and the available options71 and should have access to an appeal and review process. Children in families should also be kept informed at each stage of the process and their views taken into consideration in line with their age and maturity. | ✓ | ✓ |

| BID report. The BID manager relying on information gathered from the country of origin assessment, home study report for unaccompanied children and other experts working with the child such as the social worker and guardian drafts the BID report which should also capture implementation of the sustainable solution. During this process, information sharing between the host country and country of origin child protection and social welfare actors should be ongoing. Information shared between national authorities should adhere to established transnational data-sharing protocols including data confidentiality and privacy. | ✓ | ✓ |

Arriving at a sustainable solution informed by the BIP in the country of origin: Ethiopia

Many children in Ethiopia leave their home for a variety of reasons including poverty, persecution, gender and social discriminatory norms, peer pressure, compulsion to support the family or ease their burden and aspirations that they feel cannot be met in their village. They travel along migratory routes that may put them at risk of violence, abuse and exploitation, including child trafficking. In the Tigray region, 360 children were recorded to have left a particular district (“Woreda”) at the end of 2019. These children aim to reach the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia through Djibouti and Yemen. Many of them are intercepted in transit in Yemen and assisted or forced to return to Ethiopia. Two teenagers who joined other migrants to attempt the journey to Saudi Arabia were intercepted by law enforcement authorities before they set sail for Yemen and taken to a Red Cross shelter in Djibouti.

From the shelter in Djibouti, IOM provided transportation assistance to the teenagers to facilitate their return to Addis Ababa, as part of their voluntary return and reintegration programme. Reception was provided at the IOM transit centre for temporary shelter, support and child protection services with additional support from UNICEF. At the transit centre in Addis Ababa, once children are received, depending on the amount and quality of information shared in advance by the IOM mission, each child is profiled to verify their available data. Following identification, profiling and case counselling conducted by a social worker, an assessment of the child’s short, medium and long-term needs including family tracing is undertaken leading to a BID. The conclusion of the teenagers’ BID, conducted through an individual procedure, was family reunification.

The teenagers were escorted to their Kebele (the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia) by a social worker from the transit centre and received by a social worker from their Kebele who verified their origin and contacted the families through the Kebele community service worker. The children were reunited with their families and their case files handed over to the Kebele community service worker for follow-up implementation of their care plans.

The community service worker first assessed how the children had settled back with their families and secondly followed up with their care plans. One of the teenagers wanted to open a small kiosk in the market area while the other one wanted to engage in small scale goat rearing. The community service worker accessed the family’s criteria to obtain small loans and approached the local Community Care Coalition (CCC) for financing for the business ventures proposed. CCCs are voluntary community level structures at Kebele level that provide support to identified vulnerable members of the community including loans and grants for microeconomic activities.72 CCCs are part of the less formal child protection structures at community level in Ethiopia supported and supervised by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

- Strengthen stakeholder collaboration to support timely identification and assessment.

- Involve community service workers in the implementation of reintegration assistance, monitoring and follow-up due to their closeness to the community and critical role in identifying and facilitating available support for vulnerable children in the community.

- Facilitate child participation throughout the return and reintegration process.

- Engage less formal child protection structures in developing contexts at the community level to reinforce economic, social and psychosocial dimensions of reintegration.

6.2.2.3 Reintegration planning

Reintegration is not a single event, but a longer process involving extensive preparation and follow-up support.73 Basic planning for reintegration should inform the return decision and accelerate when return has been determined to be in the best interests of the child. The detailed reintegration plan should be developed in coordination with the child and family in the country of origin by the social worker, case manager or service delivery organization responsible for reception. Care should be taken to provide accurate information about available services based on current service and stakeholder mapping. The following considerations are recommended during the reintegration planning process which should ideally commence in the host country but can also take place in the country of origin in the case of forced returns (see Chapter 6.1, key considerations checklist for guidance on specific questions to explore).

| Protecting the rights of children during the reintegration planning process |

UASC |

Children in families |

|---|---|---|

| Safeguarding of children. This should be ensured before and during the return and reintegration process. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cross-border communication between the host country and the country of origin. Cross-border communication facilitates the case management process and marks the start of reintegration assistance. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Provide updated accurate information on the reintegration options and conditions in the country origin. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Discuss and ascertain the returnee child and family's wants and needs, covering the economic, social and psychosocial dimensions. This can include but is not limited to economic and vocational training, access to education, health care, housing, social services, documentation, food and water, and psychosocial services. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Identify who should meet the identified needs, what should happen to meet them, and when the actions should take place. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Confirm the family and household is safe for the child and investigate any present or past situations of violence and abuse. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Review family and close relationships of the child including length and effects of separation for unaccompanied children, and the capacity of parents, care givers and other close relationships. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Consider the child’s identity and development rights such as actions to meet their physical and mental health needs, access to education and vocational training for older children, in accordance with their age, sex and other characteristics and engagement in recreational activities in line with the child’s age, sex and other characteristics, linguistic background and cultural upbringing. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Active consideration of the child’s views including providing timely and accurate information, an assessment of the child’s understanding and maturity and what weight to place on their views. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Consider immediate, short-term support (one-off or several weeks) versus long-term (several months or one to two years) planning with provision for periodic monitoring whose frequency is based on the level of risk and needs of the child. | ✓ | ✓ |

If possible, children and families should sign off on the reintegration plan and copies should be made available to them for their follow-up. The components of a reintegration plan should include immediate assistance such as the provision of basic needs, medical and cash assistance and long-term support focused on the social, economic and psychological dimensions (see Annex 3 of the Handbook which outlines a Reintegration Plan Template).

Economic reintegration assistance

Returnee children and families can face numerous challenges upon return due to security issues, potential recruitment or enslavement by armed groups, possible requirements to repay debts incurred for the journey, and poor access to education and livelihood opportunities, among other concerns. The resilience of parents has been highlighted as a key factor for families receiving assisted voluntary return and reintegration assistance who contend better with challenging circumstances upon return. It is noted that if parents are resilient, their children tend to cope better as well. Economic reintegration assistance can promote resilience through creating or strengthening income-generating activities, opportunities for microfinancing, collective or community initiatives, job placement, skills development and vocational training. For youth who used to work prior to return or those who are of working age and want to engage in income-generating activities, a reintegration grant can be provided, which needs to be carefully assessed. Generally economic reintegration assistance should supplement capital for existing family businesses or help families in establishing an income-generating activity. It can also include job placements. Economic reintegration measures should fit the specific needs and skills of the returnee, the local labour market, the social context and the available resources and should be accompanied by a healthy social life and psychological state (see Module 2, Chapter 2.4 for an overview of the various types of economic reintegration).

Social reintegration assistance

assistanceSocial reintegration assistance involves direct assistance and referral to appropriate services guided by formal and informal national, local or community referral mechanisms. It includes housing, educational and social support, access to health care, birth registration and legal documentation, skills development, legal services, social protection schemes, childcare, special security measures, interim and alternative care options, family tracing and reunification, parenting classes and access to justice (see Module 2, Chapter 2.5 for an overview of the various types of social assistance recommended for a reintegration plan).

Psychosocial reintegration assistance at the individual level

Provision of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) is a critical component of reintegration assistance and involves individual, family and community-level activities. Distress caused by or during the migration journey can impact children’s ability to cope, if only temporarily. MHPSS services allow children to engage in the reintegration process and gives them the tools and space to recover after periods of distress or separation. Different children will need varying levels of mental health and psychosocial support and a few children may need specialized MHPSS interventions. Mental health and psychosocial needs range from basic services which can be made available on a more universal basis to specialized services for people with previous or emerging mental health issues. Most people when provided with a safe, protected and nurturing environment after a period of distress will have the resilience to bounce back given some time. The focus should not be on providing specialized services right away but on fostering resilience through appropriate activities and promoting a conducive environment

6.2.2.4 Implementing the reintegration plan

A family-centred approach that identifies the needs of the child and focuses on strengthening the capacity of the family to protect and care for the child is crucial to achieving sustainable reintegration. Ideally, reintegration assistance should commence in the host country and continue in an interconnected manner in the country of origin through the sharing of the initial assessments, identity documentation, education and skills certificate as appropriate. However, the assessment and reintegration plan should cater to whatever stage of the migration journey the child is identified, whether it is in transit, in the host country or upon return to the country of origin.

The appointed social worker, case manager or case worker should work with the child and family throughout the case management steps unless a specific qualification is recommended during the process or the child and the family are unhappy with the case worker. Ultimately the case manager or social worker is responsible for following up on the case plan and the service provider to ensure that the needs of the child have been met.

| Protecting the rights of the child during implementation of the reintegration plan |

UASC |

Children in families |

|---|---|---|

| Direct services such as psychosocial support or parenting programmes can be provided by the social worker, case manager or case worker or accessed through referral to available service providers. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Facilitate routine child-friendly consultations with the child and family to review actions and progress. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Refer children and families to appropriate services covering the economic, social and psychosocial dimensions proposed in the reintegration plan. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Economic and vocational training. If economic assistance is deemed an appropriate support option, facilitate the provision of income support to families (or to the child directly depending on their age, applicable legislation and policies) for basic needs to address multiple drivers of family-child vulnerabilities which may contribute to root causes of family separation or triggers of irregular migration. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Access to health care. Assist children and families in accessing required medical assistance. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Access to documentation. Assist children and families in obtaining civil registration documentations such as birth registration and other documents needed such as school transcripts. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Remain updated on existing services, referral mechanisms and networks with documented referral pathways and focal points, to facilitate access to appropriate services. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Confidentiality and privacy should be maintained through agreed standard operating procedures and protocols among referral partners including obtaining consent from the child and family to share information for referral to appropriate services and the transfer of case files. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Target support for complex vulnerabilities. Assess and provide additional targeted and specialized support to children with intersecting vulnerabilities such as unaccompanied or separated children, adolescent girls, pregnant teenagers and teenage mothers, those who have experienced being trafficked, violence, abuse and exploitation, children with HIV/AIDS, children with disabilities and other children with complex needs.74 | ✓ | ✓ |

6.2.2.5 Follow-up and review

The purpose of the follow-up and review is to make sure that the case plan is being implemented in accordance with agreed actions and continues to meet the needs of the child and family. Follow up and review should be conducted routinely with the child, family and other stakeholders to review progress, confirm service provision, identify gaps, assess whether the reintegration plan continues to meet the needs of the child, and where necessary review and modify agreed actions. The frequency will depend on the level of risk, and whether the case management process is focused on immediate, interim or long-term actions. Follow-up can be as frequently as daily, while review takes place over a period of time ranging from several months to two years or more and involving a multisectoral and interagency approach. Follow-up can be conducted through phone calls, meetings with the child and family, home visits; or through community mechanisms supporting the child, such as a health worker, teacher or community worker. Review provides an opportunity for the child, case manager and the supervisor to assess progress of implementation and whether the child or family require additional or a variation of services.

Follow-up and review can be adapted as case management progresses and the situation of the child improves. The table below illustrates actions that can be subjected to periodic follow-up and review.

| Follow-up and review |

UASC |

Children in families |

|---|---|---|

| Routine child friendly consultations. The social worker or case worker should facilitate routine child-friendly consultations with the child and family to review actions and progress. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Improved home environment. Support parents to implement strategies and knowledge gained in parental classes resulting in improvement of the home environment. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Economic and vocation training. The case worker should regularly review the status of the income-generating activity or vocational training and adjust. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Access to health care. Children and families have access to required medical assistance or have reported back barriers which are being addressed. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Access to documentation. Parents are able to access the civil registration and vital statistics office to obtain birth registration and other civil registration documentation, and other offices for relevant documentation such as school transcripts. | ✓ | ✓ |

| Continuous assessment. Consider immediate, short-term support (one-off or several weeks) as well as long-term (several months or one to two years) planning with provision for periodic monitoring whose frequency is based on the level of risk and needs of the child. Assess and review existing and arising risks to the child and family. | ✓ | ✓ |

6.2.2.6 Case closure

Case closure occurs when the child and family’s reintegration has been met, appropriate care and protection has been identified and is ongoing and there are no further additional concerns. A case can also be closed in the following situations:

- The child and family no longer want support.

- The child turns 18. A period of transition and connection to independent living and other services is however recommended.

- The child dies.

Case closure should be authorized by the case manager and require that monitoring visits continue thereafter for at least three months depending on the complexity of the case. Case records should be stored in a safe and secure manner for a defined period in accordance with existing agency protocols and national legislation.

Multidimensional reintegration assistance for returnee children in Côte d’Ivoire

In Côte d’Ivoire, IOM regularly assists Unaccompanied and Separated Children, children returning with their parents, as well as single mothers. Between May 2017 and August 2020, IOM assisted 539 children returning with their parents and 162 unaccompanied and separated children, 11 per cent of the total number of returnees assisted through the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration.

For unaccompanied and separated children, the BIP and family tracing takes place before the child returns to Côte d’Ivoire. Upon arrival, once children are reunited with parents or guardians, the IOM protection and reintegration teams screen the parents and the child through counselling sessions to understand the specific family situation. As part of this project, during these counselling sessions the child, parents and IOM staff work together to develop a holistic reintegration plan that considers the economic, social and psychosocial dimension of not only the child but the entire family.

For the social dimension, which is often the most urgent need, IOM staff help children and their families to access medical services as needed, through an IOM doctor; referrals can be made to specialists. A specialized shelter is available for unaccompanied children who cannot reach their parents immediately. If a returning family needs to find housing, IOM can help to cover the security deposit and rent for the first three months. IOM staff also assist in enrolling children in school, in many cases covering school fees for a few years at a time, so that children are more likely to remain in school.

For the economic dimension, IOM staff work with the children’s parents to establish or supplement existing income-generating activities. Young people who want to earn an income rather than go to school are encouraged to take part in vocational training in sectors that have been identified as promising, such as mechanics or agriculture, following an initial mapping.

For the psychosocial dimension, psychoeducational group sessions have been organized for returned unaccompanied and separated migrant children in Abidjan and Daloa, in addition to individual sessions with an IOM psychologist. These groups give the opportunity to offer a safe space for open dialogue, free discussions on challenges, dreams, plans for the future, education, psychosocial difficulties, and have the benefit of strengthening peer-to-peer support mechanisms and resilience. Other psychosocial groups, including art-based and creative therapeutic methods such as group drawings sessions, have also been organized for accompanied minors (aged 3–12 years old) and their parents.

Single and pregnant mothers have been identified as a particularly vulnerable group, since they often return with very young children and therefore require more intense case management. For example, IOM provides them with kits for their young children and assists in covering childcare costs to allow the mothers to work.

Follow-up with the children and their parents is carried out regularly by a joint IOM protection and reintegration team.

- Develop a reintegration plan that takes into account the entire household that the child lives with;

- Emphasize the psychosocial dimension which can positively influence the other reintegration dimensions;

- Establish a network of partners and services in areas of high return to facilitate swift referrals.

64 The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, Minimum Standards for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, p. 200 (2019).

65 Inter Agency Guidelines for Case Management and Child Protection, The Role of Case Management in the Protection of Children: A Guide for Policy & Programme Managers and Caseworkers (London, 2014).

66 Catherine Moleni, Sofie Project, Institute of Education, London, Guidelines for Counselling Children and Adolescents: A Training Manual for Teachers and SOFIE Club leaders (London, 2009).

67 Ibid.

68 UNCRC, General Comment No.6, 2005.

69 Natalia Alonso Cano and Irina Todorova, Towards child-rights compliance in return and reintegration, Migration Policy Practice: Special Issue on Return and Reintegration. Vol. IX, Number 1, January–March 2019; pp. 15–21.

70 Family tracing and assessment should be conducted unless determined not to be in the best interest of the child. See: EC, Comparative Study on Practices in the Field of Return of Minors (2011), p. 166.

71 European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Returning unaccompanied children: fundamental rights considerations (Vienna, 2019).

72 Community Care Coalitions (CCCs): Community organizations formed by a group of individuals or organizations to provide care and support to vulnerable people. The goal of CCCs is to foster resilient communities that develop local strategies, identify resources, prevent and respond to vulnerabilities at community level, strengthen social capital and promote social norm changes. The specific objectives of the CCCs include: strengthening economic capacities of the vulnerable, strengthening social capital to promote mutual support, promoting social norm change, supporting vulnerable people to access basic social services, social protection and legal services, mobilize local resources and supporting the development endeavours. Government of Ethiopia Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, National Strategic Framework for Community Care Coalitions, authored by BDS Center for Development Research, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (August, 2018).

73 Delap, E. and J. Wedge, Guidelines on Children’s Reintegration, p. 7 Inter Agency Group on Children’s Reintegration (2016).

74 UNGA Seventy-fourth session, 26 July 2019 Report of the Secretary General, Status of the Convention on the Rights of the Child: Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Children (United Nations, New York).